Chapter 4, Part 1 - Interpreting Scales

A scale is a collection of tones. We like to think of it as a ‘tone palette’. The whole topic of ”Scales” can be overwhelming for students of Jazz. We offer here what might be a new way to approach the topic of scales as it relates to Jazz.

We will be taking an integrated approach to scales, exploring how they relate to intervals, chords and ultimately, chord progressions. We will start by looking at some scales that can be formed by stacking intervals. This will generate some Symmetrical Scales. The next section will look at Compound Scales, made up of various intervals. Then we will touch on some scales we call Stylistic Scales. We will finish by seeing if there are any conclusions we can draw.

Note: Scales are not meant to impose restrictions or limitations on our creativity. A painters palette doesn’t decide what the painting will look like. Unfortunately, there are far too many theorists and educators that treat scales like a set of rules. Scales can help describe a musical style or inspire new areas of exploration but they can not replace “playing what ya hear”.

Symmetrical Scales

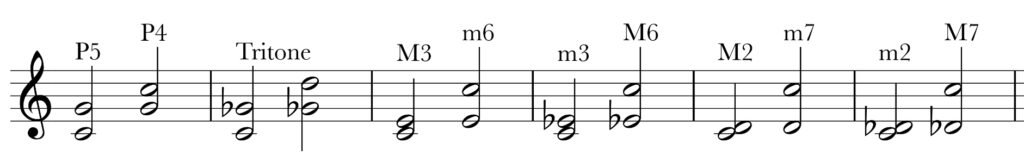

As we have discussed before (Link), being able to hear, identify and reproduce any interval at will is the key to playing creative music. Spending time developing this skill is essential, in our view. As we did when analyzing chords (Link) we will start by looking at some stacked intervals. Example 1 shows us all available intervals with their inversions.

Minor Seconds

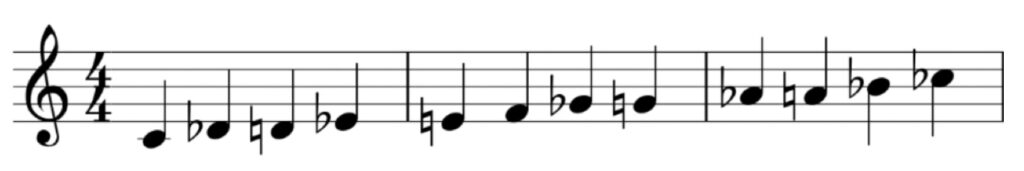

Stacking minor second intervals creates the 12 tone or “Chromatic scale“(Example 2). It is the main tone set in Western music. We will return to this set in a moment, but for now notice that it is a symmetrical scale dividing the octave into 12 equal parts.

Major Seconds

Stacking Major second intervals gives us a six note scale called the “Whole tone scale” (Example 3). There are only two whole tone scales (find the other by starting on ‘b’). It’s another symmetrical scale. As with all symmetrical scales, each tone is of equal importance. None of the tones “pull” to any other tone. Symmetrical scales are useful because of this ambiguity; they can perform a number of different functions at the same time. Notice the scale can be seen as two augmented triads a tone apart.

Minor Thirds

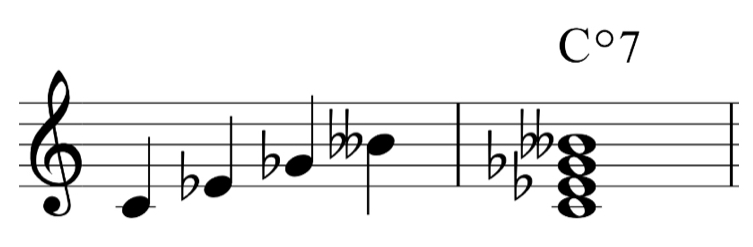

A stack of minor thirds gives us a four note set before repeating. It is, again, symmetrical. The set creates a Diminished Seven chord. The minor third is structurally very important as we will see in a moment. It is interesting to note that the diminished triad is not symmetrical (C-Eb-Gb). In fact, because of the tritone interval (C-Gb) it has a very strong pull (to Db-F). The diminished triad is very directional while the diminished seventh is indeterminate.

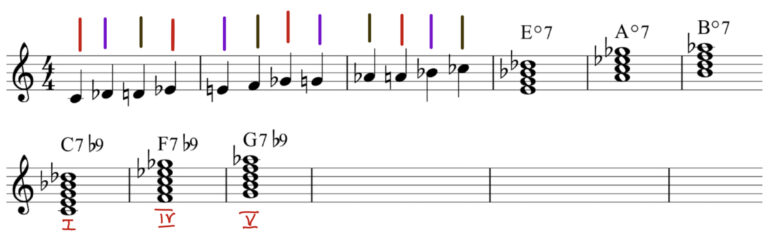

If we group the Chromatic Scale into a set of minor thirds we get three diminished 7 chords (Example 5). Both Arnold Schoenberg and Walter Piston, two of the most important theorists of the twentieth century, viewed these chords as dominant 7th, flat 9 chords with the roots implied. This is very interesting because these chords relate to each other as I-IV-V, which of course is the basic chord group for the blues. Challenge: try writing a twelve tone blues song!

Major Thirds

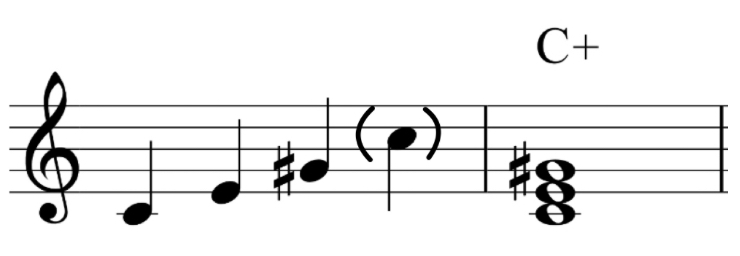

A stack of Major thirds gives us a three note set before repeating. Again, it is symmetrical. The set creates an Augmented triad. It relates directly to the Major second series in that it describes a part of the Whole Tone Scale and every triad of the Whole Tone Scale is an augmented chord.

If we group the Chromatic Scale into a set of Major thirds, like we did with the minor thirds, we get four augmented triads (Example 7). These distinct sets are the bases of what have come to be called the “Coltrane changes” or “Giant Steps changes” (Link).

Perfect Fourths & Fifths

Stacked 4ths and 5ths run through all twelve tones before repeating. They form four 3 note chords a minor third apart.

The Pentatonic scale is included here because of its relationship with stacked 5ths. It is not symmetrical but it can be viewed as a stack of five perfect 5th intervals. The scale shares some of the features of symmetrical scales because it has no “restless” minor second intervals making it stable and “complete” but also somewhat ambiguous.

1/2-W & W-1/2 Scales

We should mention two more symmetrical scales that are actually “compound” in that they combine different intervals: The Half-Whole and Whole-Half scales. As the names implies, they alternate minor 2nds and major 2nds (Example 11). The 1/2-W version is more common as it works well with dominant seven chords and the Blues.

Back: Chapter 3 – Chords.

Next: Part 2 – Compound Scales.

Skip to Chapter 5 – Aural Logic.