Chapter 2 - A New Approach to Jazz Intervals

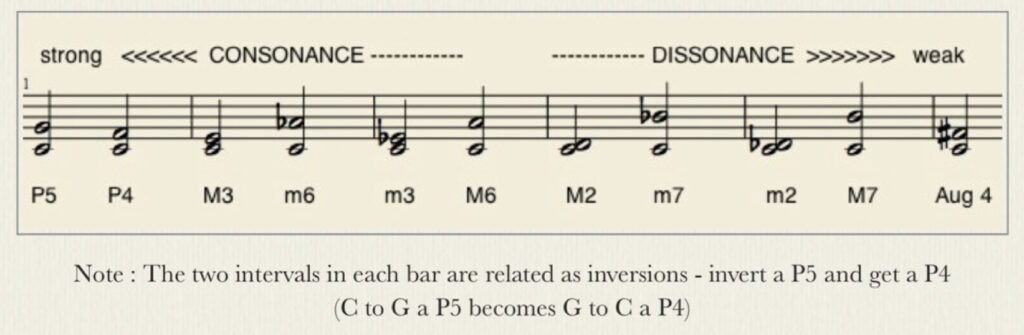

Traditionally, intervals have been organized by their subjective consonance (Example 1). This treatment of dissonance remains an inescapable part of Western Tonality. After WWII, Jazz musicians began using the four note 7th chords as foundational and used exposed ‘altered upper-structure extensions’ extensively (b9, #9, #11, b13)

“Dissonance” became normalized in Jazz, leading to, what Arnold Schoenberg called, the “emancipation of dissonance”. Schoenberg contends that “what distinguishes dissonance from consonance is not a greater or lesser degree of beauty, but a greater or lesser degree of comprehensibility“. We are going to concentrate here on the relationships between different intervals. For instance, we treat the often demonized Tritone as an extension of the minor third rather than the “most dissonant of intervals” (Note: Persichetti contends the tritone is ambiguous. It can be either neutral or restless). We will group all possible intervals into three groups: the Perfect Group, the Thirds Group and the Seconds Group.

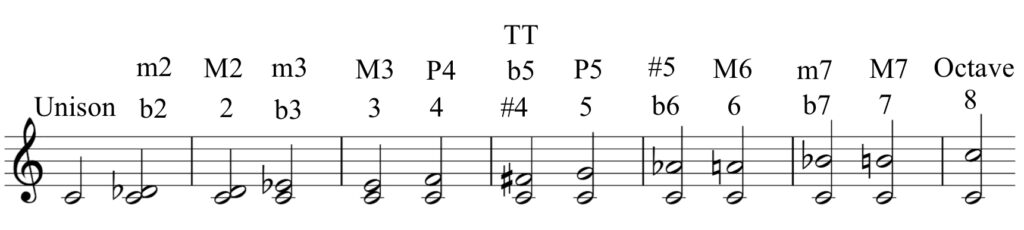

Note: Our discussion of intervals is based on the pitches as they sound on the piano. The system of 12 Tone Equal Temperament makes “Enharmonic Equivalence” possible, for example f-sharp is the “same” as g-flat. Context dictates how a pitch is named. Exploring this page should help get some of the quirky terminology down.

Here are the intervals smallest to largest within the octave (Example 2). ‘m’ equals minor, ‘b’ equals flat, ‘M’ = Major, P = Perfect, ‘TT’ = tritone, ‘#’ = sharp.

The minor 2nd is a “half step” or “semitone”. A Major second is a “step”, a “tone” or a “whole tone”.

The Perfect Group

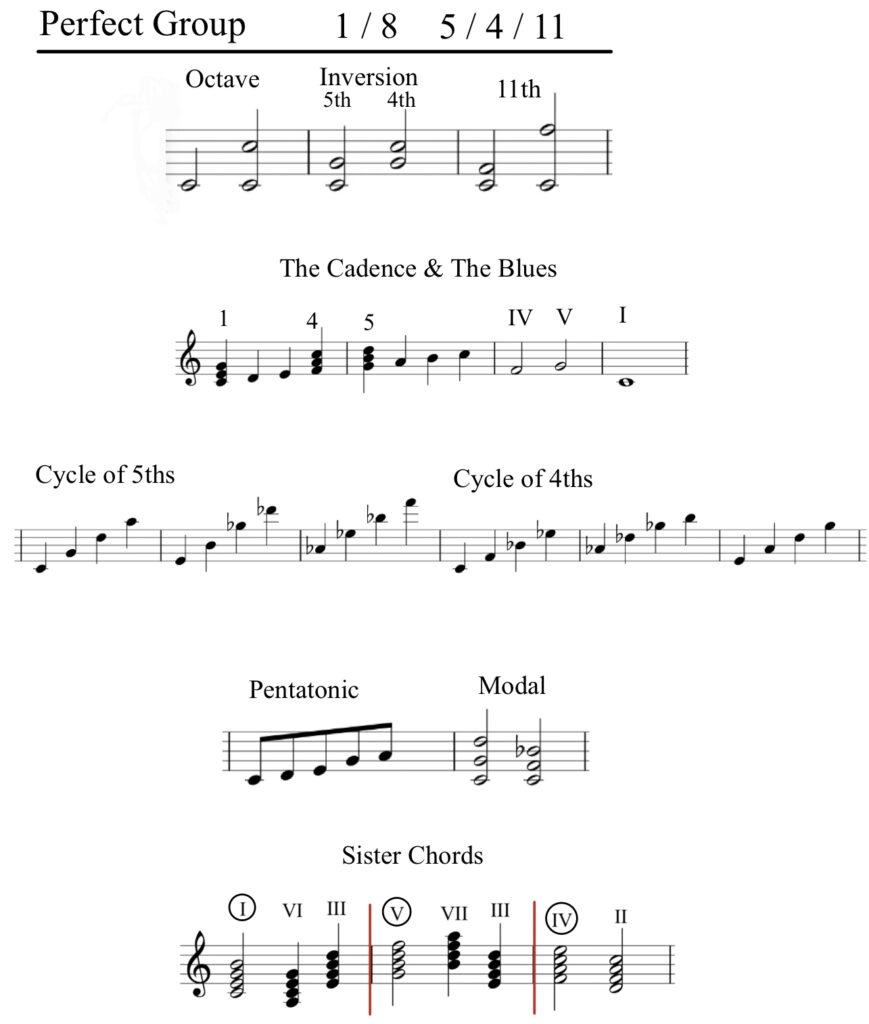

The Perfect Group is foundational in most music cultures, none more so than Jazz. Pitches played in unison or separated by an octave add importance to those notes relative to other sounds being played at the same time. The fifth is the most prominent overtone, so it literally sounds itself when a pitch is played! The inversion of a fifth interval is a fourth (Example 3, line 1). Playing the top note of a 4th an octave higher (displaced) gives us the 11th (we will get into these “upper structures” when we talk about chords (Link).

The “Major Scale” and chords made from stacked thirds are the foundation of Western Tonality (Example 3, line 2). ‘Diatonic’ (using only the notes in the scale) Major chords are only found on the first, fourth and fifth degrees of the scale (I, IV and V). Typically, these chords are used to end musical sentences (cadences). These three chords are also the bases of the Blues (Link).

The “Cycle of Fifths” is employed in a huge number of Jazz songs. These “Changes” (chord progressions) built on 4th / 5th intervals play a huge role when Jazz is promoting or challenging Tonality.

The Pentatonic scale is a rearrangement of 5ths (Link). Chords built on 4ths and 5ths are used in “Modal Jazz” (Link). Sister Chord groups are based on I, IV and V (Link).

So, the Perfect group is important in Rudimentary or Roots music and “World Music”. Roots music saw a revival in the avant-garde music of the 1960s. The root and fifth sounds the oom-pah of stride piano. Power chords in rock are built on 5ths.

The Thirds Group

The Thirds Group divides into two sub-groups minor thirds or flat three (m3) and Major thirds (M3).

The minor third is a building block of a number of important Jazz concepts. An inverted minor third forms a Major sixth (Example 4, line 1). The displaced minor third gives us the enharmonic sharp nine. The displaced Major sixth is a thirteenth (Link). A minor third and a perfect fifth makes a minor triad.

A stack of two minor thirds forms a Tritone (#4, b5). The tritone splits the octave into two equal parts. A displaced tritone forms a #11. A stack of three minor thirds gives us the Diminished Seven Chord. The dim7 is symmetrical which makes it indeterminate – each inversion of a dim7 is a different dim7 chord. Very useful for changing harmonic direction or being intentionally ambiguous.

The chromatic scale can be formed by combining three dim7 chords (Link).

The minor third and flat five are at the heart of two of the three blues “flex-tones” (Link).

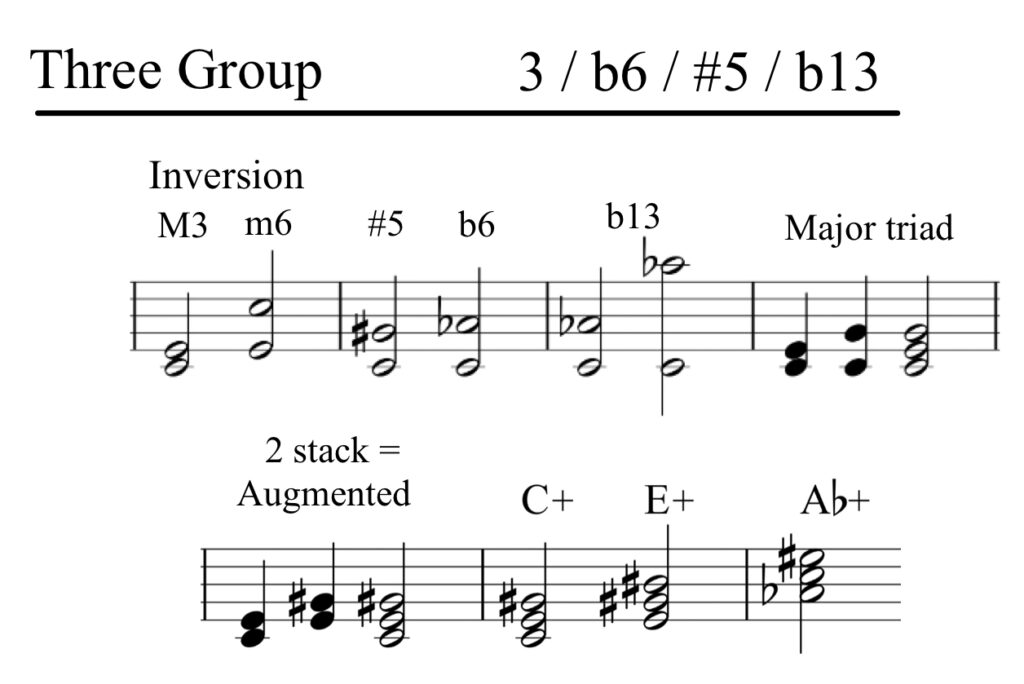

The Major third group is not quite the multi-tool that the minor third group is. An inverted Major third makes a minor 6 (Example 5, line 1). The sharp five / flat six is the same distance as two Major 3rds. A displaced b6 is a b13. A Major triad is a M3 and a P5.

Two stacked Major 3rds make an Augmented triad. The aug triad is symmetrical and indeterminate – inverted it forms two new aug triads (Example 5, line 2).

Major 3rds is how John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’ changes are arrived at.

The Seconds Group

As with the thirds the seconds split into minor seconds (semitones) and Major seconds (whole tone).

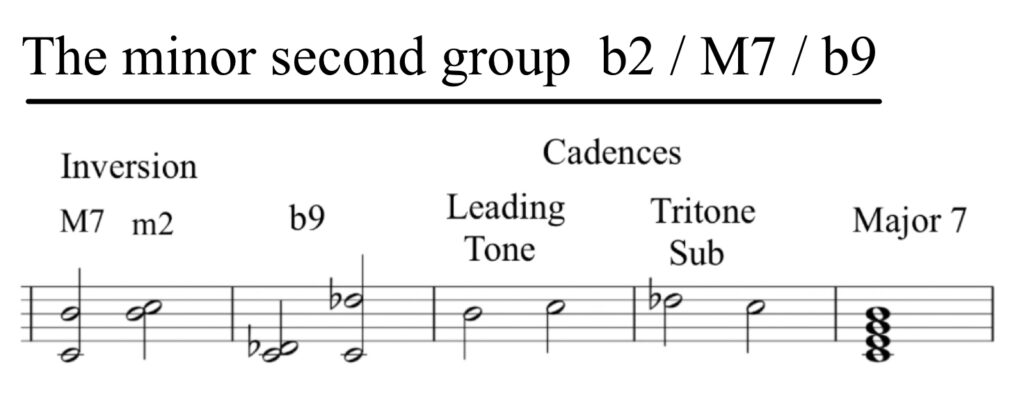

An inverted minor second is a Major seven (Example 6, line 1) A displaced m2 is a flat 9.

The relationship between the seventh degree of a major scale and the eighth degree (8 = 1 = tonic) is important because the tonic is “home” and the M7 is the closest diatonic (in the scale) note to home; it is called the ‘leading tone” and it is an important part of the most common cadence (V-I). We will also see that another common Jazz cadence approaches the tonic from above by a half step (the tritone substitution).

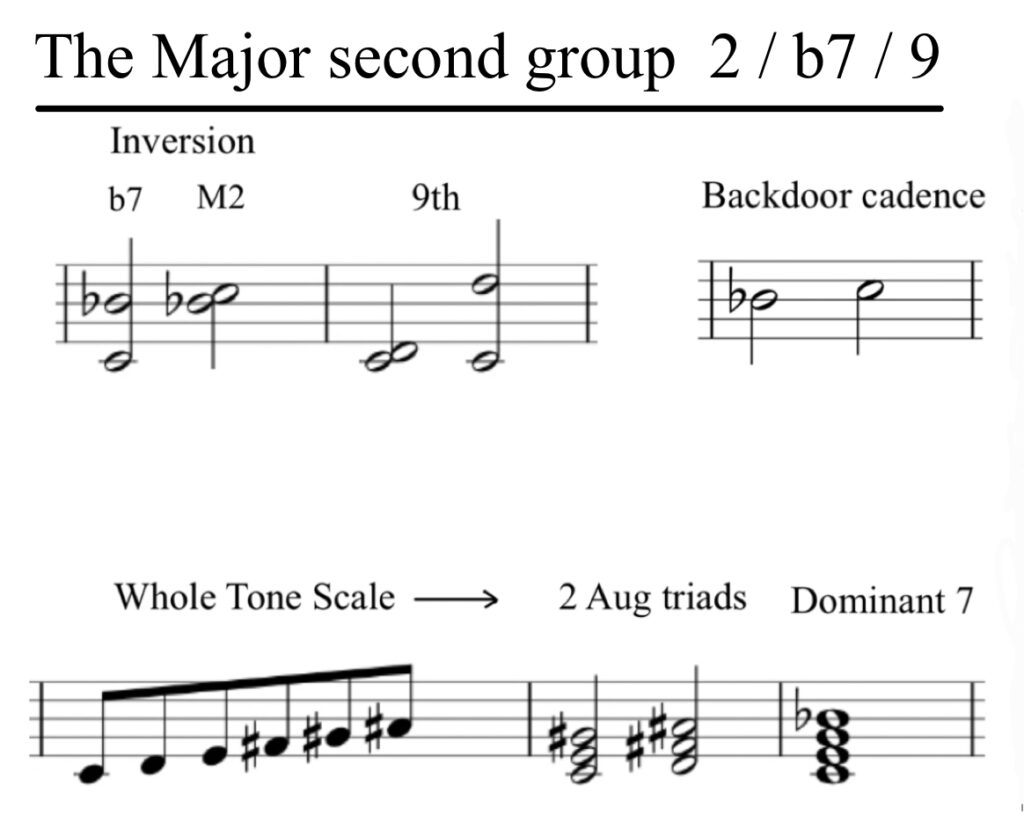

An inverted Major second makes a minor seven (Example 7, line 1). A displaced Major 2 yields a ninth.

Another cadence used in Jazz approaches the tonic from a whole tone below. It has come to be known as the “Backdoor Cadence”.

A series of Major second intervals makes a “Whole Tone” scale. A whole tone scale can also be made by combining two Augmented triads a tone apart.

Conclusions

This is clearly a lot of information to absorb but there are two main objectives here:

(1) There is nothing more important for an improviser than a thorough understanding of intervals. The more players can quickly identify intervals when they hear them, or sing any interval at will, the closer they will be to inventing on the fly.

(2) Playing and thinking about intervals from different points of view reveals relationships that can be exploited when composing and improvising.

“Our Analysis” approaches these same concepts chronology (a lot more fun!). Find tunes you like and come back to this page often for reference, cross-reference and inspiration. Good luck!

Exercise: Try finding “reference songs” – songs that are very familiar to you that have intervals you want to be able to pick out anywhere. ‘Pink Panther’ is a good example. It has Perfect fifths and fourths, minor seconds and Major sevenths, minor and Major thirds and the Tritone. Call it something like “the panther minor second”.

Back: Chapter 1 – Rhythm

Next: Chapter 3 – Chords Part 1