“Rhythm is life the space of time danced thru.” Cecil Taylor

Chapter 1 - Rhythm

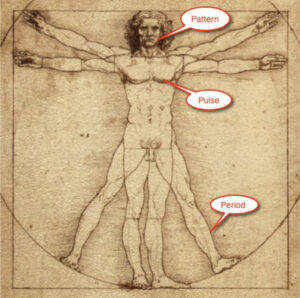

Rhythm has three constituent parts: Pulse, Period and Pattern. The interplay between these three distinct components is one of the distinguishing features of Jazz music.

Jazz has always been a mixture of diverse musical sensibilities. The earliest hybrid forms combined the music of primarily Britain, Scotland and Ireland with that of Ghana and Nigeria. One was notational, the other oral. One was based on “Divisive” metre the other “Additive”. The melding of these seemingly incompatible approaches to music making created a unique musical form. We will first look at each rhythmic component separately and then look at how the parts interact in Jazz.

Pulse

“Pulse”, as we will define it here, is rarely mentioned in traditional Western music analysis. But let’s start with the dictionary definitions of Pulse:

(1) Pulse is “the central point of energy and organization in an area or activity.”

(2) At it’s most basic, rhythmic Pulse is simply the Beat or the “main accent or rhythmic unit in music or poetry”. In South Indian music it is called “Laya“. Like Pulse itself, Laya is said to be “a simple concept though complicated in application.”

(3) Pulse is a “kinetic, propulsive force producing movement”.

Musical Pulse and Poetic Cadence

The terminology typically used to describe musical rhythm fails miserably when we try to talk about ‘Pulse’. This is particularly surprising when we realize the concept is something we all understand instinctively (see below).

Luckily, the concept of ‘Cadence’ as it applies to poetry works very nicely as a synonym for ‘Pulse’.

(1) Cadence is “the beat, time or measurement of rhythmical motion or activity”. It is “a rhythmic sequence or flow of sounds in language”. Cadence is the “rise and fall in the natural flow and pause of ordinary speech, without distinct metre“.

(2) Cadence is the “organic rhythm – not metre – rather the rhythm of the speaking voice with the necessity for breathing“.

(3) “It occurs in free verse poetry and prose as well as structured poetry.

Pulse as a Wave Form

The Pulse is literally inside you. In the 15th and 16th century, musical “beat” was called “tactus”. Gaffurius (Practica musice, 1496) said that “tactus equaled the pulse of a man breathing normally”. Think of the cardiac cycle – systole/diastole (lub-dub).

Jazz flute player, Herbie Mann said “find the waves that you are comfortable to float on top of”. We will come back to this when we talk about the Interplay between Pattern, Period and Pulse.

The visual manifestation of Pulse can be seen in the swaying or rocking motion of a African drum ensemble, a woman singing a lullaby to her baby, or the rolling cadence of a southern preacher or of a Martin Luther King speech. 20 seconds into this video clip you can see an audience member swaying to the musics pulse.

Period

if we measure musical time or “mark” time we introduce “Period“. In the West, period is usually referred to as Metre. Period is independent of Pulse and Pattern. In Indian music Pulse is ‘Laya’ and Period is ‘Tala’. Period is the “tick-track” – a mechanical, mathematical, metronomic division of duration. Period can be ‘Divisive’ or ‘Additive’.

Divisive Period

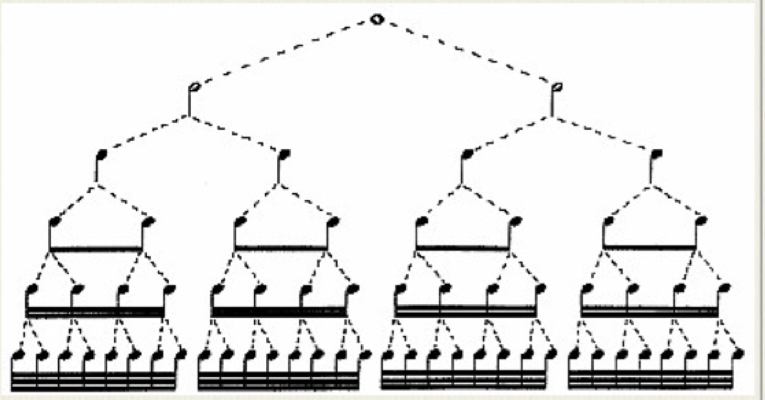

Divisive Period is most common in the West. The individual note values that are used to create ‘Pattern’ are to be regarded as divisible into smaller units and multiplicable into larger units (Example 1). This is foundational to our system of music notation.

The metronomic Period can fall precisely on the beat of the organic Pulse… but it doesn’t have to. And “Therein lies the rub” – there is no way to separate period and pulse in the western notational system.

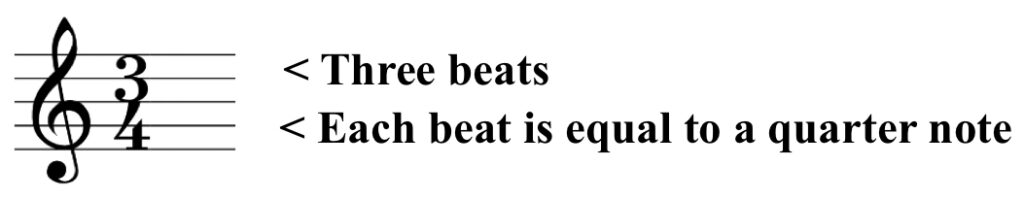

Additive Period

Additive Period is common in many non-Western cultures. The individual note values that are used to create ‘Pattern’ is not really addressed in this system (adding to the separation of Pattern, Period and Pulse). Additive Period also requires the establishment of a ‘tick-track’ but it is usually much less prominent than in Divisive Period. Period is established by choosing a number of metric units (usually 2, 3 or 4) and then combining (adding) these subunits into a larger metric group. The subunits are the “rhythm” that ultimately becomes audibly prominent (2+2+3 | 2+2+3 = short-short-long | short-short-long).

Pattern

All systems of music overlay “Pattern” over the underlying Pulse and Period. In the West these Patterns are often (unfortunately) called “the rhythm” of a piece of music. In Jazz these Patterns range from something as repetitive and prominent as a “shuffle rhythm” (triplet feel) or a Samba pattern. Or they might be a rhythmic motifs like the famous “So What” phrase (Link). Or the Patterns can be the less repetitive “language patterns” of instrumentalists or vacalists.

Interplay

So… what does this seemingly overly analytical minutiae have to do with playing Jazz rhythms? As it turns out, an awful lot. The whole evolution of Jazz music revolves around the interplay between these distinctive elements of rhythm.

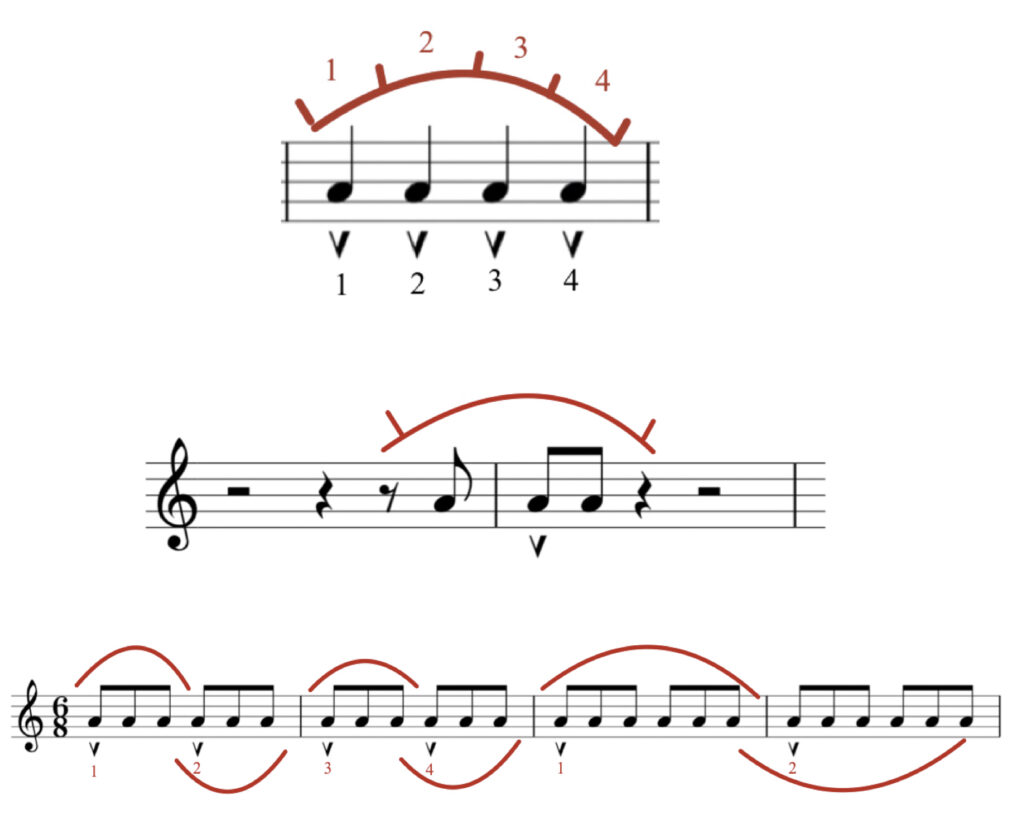

Pattern-Period

One of the earliest, and most basic, rhythmic interplays is found in “Ragtime”. This style focuses on syncopation – the play between Pattern and Period. Syncopation is the displacement of accents so that the weak metronomic units are emphasized (1-and-2-and).

Another Pattern-Period innovation is found in the so called “bebop scale”. This is almost the opposite of syncopation. The regular seven note scale is made symmetrical by adding another note. This shifts the important chord tones on to the strong metronomic division (Link).

Pulse-Period

The interplay between Pulse and Period has always been a distinguishing feature of blues music and it’s many offshoots, including Jazz. A clear manifestation of this can be heard in the flexible treatment of the strict 8 or 12 bar framework. One chorus may be 12 bars while the next might be 11 or 13 bars (Link). The most accomplished players would move effortlessly between these variations because they instinctively felt the underlying, organic Pulse or beat of the music.

“Swing” is a more flexible form of syncopation. It too comes from the interplay between Pulse and Period. As small ensemble jazz developed after WWII it allowed for even more flexibility of this interplay. The musicians didn’t have to always “swing together” anymore. A growing comfort in the grounding and unifying effect of Pulse allowed the players room to “do their own thing”. As Herbie Mann said: “find the waves that you are comfortable to float on top of”.

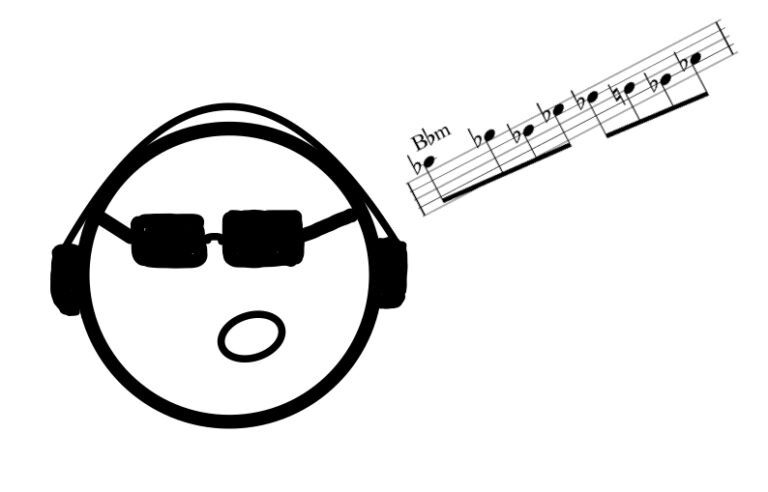

Repeatedly we have read and seen reference to how Pulse can be imagined and felt as a wave or circle. The natural cadence of pulse, when superimposed on the metric Period allows for the displacement of Patterns. As long as the musicians are sharing the “groove” of the Pulse, a great deal of expressive freedom can be enjoyed. The red “waves” in Example 2 show how note placement can be put anywhere around a metronomic period, even across bars. This elasticity creates tension and therefore interest. Even “polyrhythms’ can emerge, as the last line suggests with the concurrent feeling of 2 and 3.

Pulse-Pattern

Finally we come to what is probably the most misunderstood development in Jazz. It has been burdened with a most unfortunate label: “Free Jazz”. Lazy observers and analysts have declared this style as “anything-goes-Jazz”. It should be obvious this is not a description at all. Anyone familiar with the language knows what they are listening to after a few bars {we used to say – if you think anything goes just try playing “Mary had a Little Lamb” over and over again at a “free jazz” session and see how long you last.}

Borrowing once again from poetry, I prefer to call the music “Free-Verse Jazz’. Free-verse is defined as “non-metrical, non-rhyming lines that closely follow the natural rhythms of speech. A regular pattern of sound or rhythm may emerge in free-verse lines, but the poet does not adhere to a metrical plan in their composition. Free verse contains some elements of form, including the poetic line, which may vary freely; rhythm; strophes (a structural division); stanzaic patterns and rhythmic units or cadences. T.S. Eliot wrote, “No verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job.”

Innovators like Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor needed to find drummers that could accommodate this non-metrical music. We have a page that introduces some of these innovative percussionists that were so crucial to the musics development (Link).

“There once was a word used – Swing. Swing went in one direction, it was linear, and everything had to be played with an obvious pulse (period) and that’s very restrictive. But I use the “rotary perception” (pulse). If you get a mental picture of the beat existing within a circle of the beats in the bar at intervals like a metronome, with three or four men in the rhythm section accenting the pulse. That’s like parade music or dance music. But imagine a circle surrounding each beat – each guy can play notes anywhere in that circle and it gives him a feeling he has more space. The notes fall anywhere inside the circle but the original feeling for the beat isn’t changed. If one in the group loses confidence, someone hits the beat again. The pulse is inside you. When you’re playing with musicians who think this way you can do anything, anybody can stop and let the others go. It’s called strolling.”

Charles Mingus – “Beneath the Underdog” (the italics are mine)

Go to – Related: Pulse Drummers

Next: Chapter 2 – Intervals