Chapter 6, Part 1 - Changes

We have talked a bit about Rhythm, Intervals, Scales and Chords. Now we will try to pull it all together by looking at Jazz Progressions or Changes.

Go directly to Advanced Changes

In Search of Improvisational Freedom

“Every composition that we come up with is a means to get to a different type of improvisational area.” Bruce Ackley of Rova

“Freedom in music is the ability to know the rules in order to bend and break them to your own satisfaction and taste.” Miles Davis

Tonality

Imagine yourself in a large field with your companion way down at the other end. You want to hail him so you take a big breath and yell a high pitched sound. As you run out of breath the pitch falls and finally ends on a lower note that doesn’t need so much air to produce. No response. You take a bigger breath and start on a higher pitch thinking he will be more likely to hear the higher note. Again as you run out of breath the pitch falls to roughly the same low note because that note is comfortably in your range. This “Tumbling Strain” with its tension filled high note that comes to rest on a low note describes the essence of Tonality: tension that resolves to a common tone.

Destinational Tonality

“Tonality, in a narrow sense, is a system of tonal relationships and tonal functions, where the most important element is a tonic or central note. It is not enough to settle on a final note. It must be the centre of reference of a whole piece.” Carl Dahlhaus

This, rather strict, definition of Tonality evolved over more than 350 years (we will see some alternate definitions of Tonality in Part 2). Jazz practitioners that employed Destinational Tonality during the 1950’s and ‘60s include Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver and Duke Jordan. For a more extensive list check out this Link.

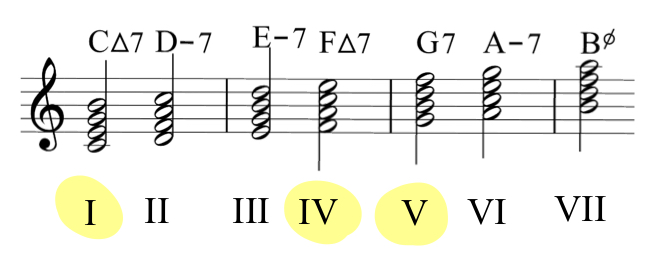

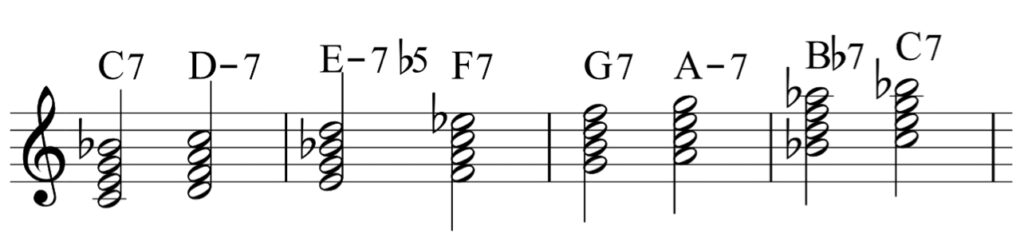

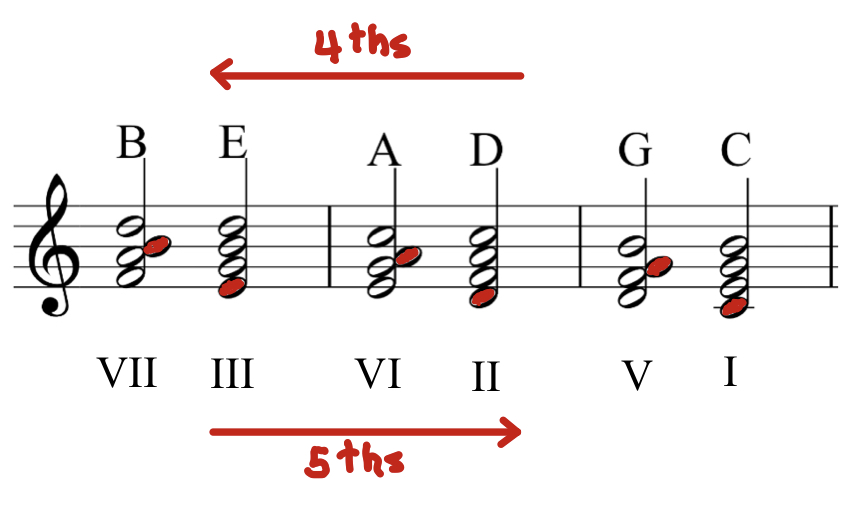

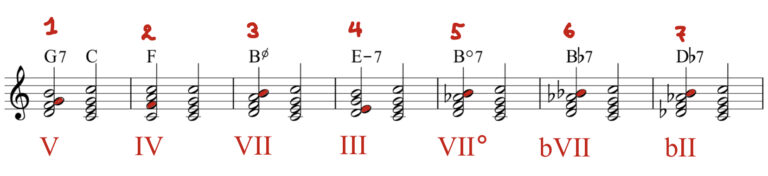

Destinational Tonality has three main components: the major scale, chords built on stacked thirds with their “roots” and “inversions” (Link), and a Roman Numeral numbering system with ‘I’ as the home or tonic. We can see there are two Major Seven chords, I and IV, and one Dominant Seven Chord, V in the group (Example 1)

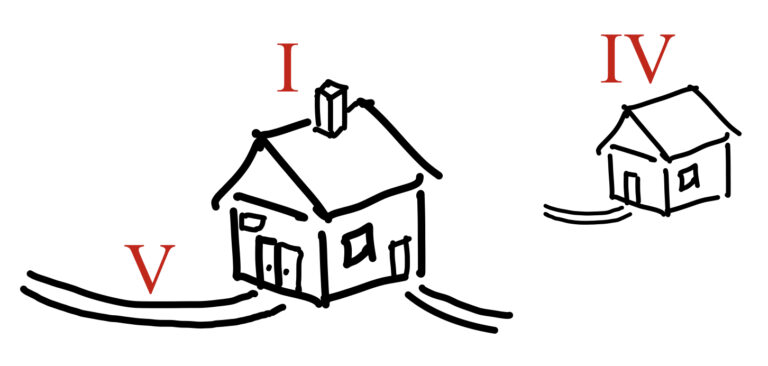

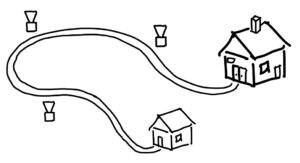

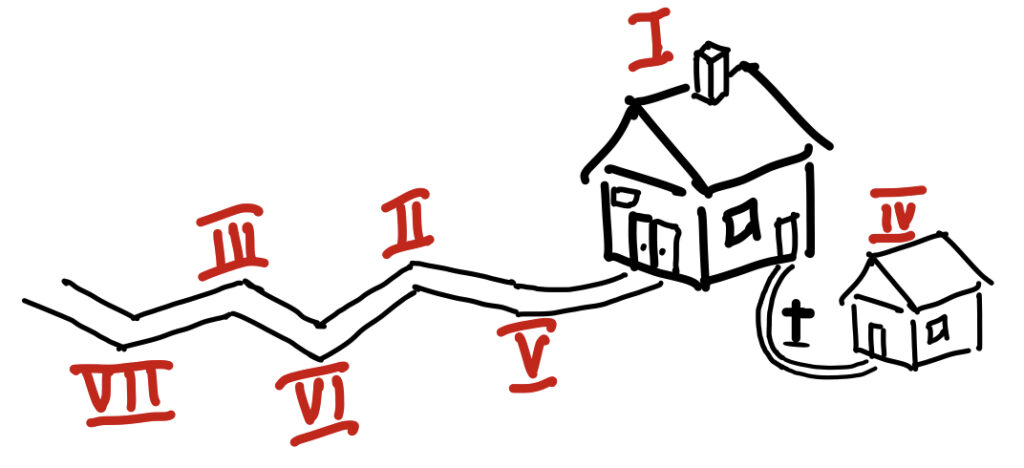

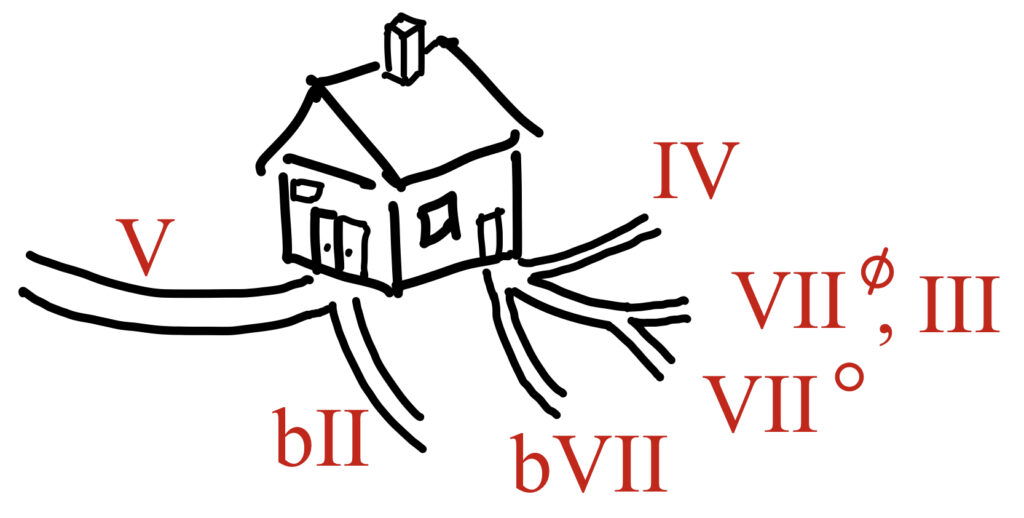

These three members of the tonal set play a central role in Destinational Tonality. ‘I’ is our home, ‘IV’ is our cottage or “home away from home”. ‘V’ is the main driveway leading to our home (Example 2).

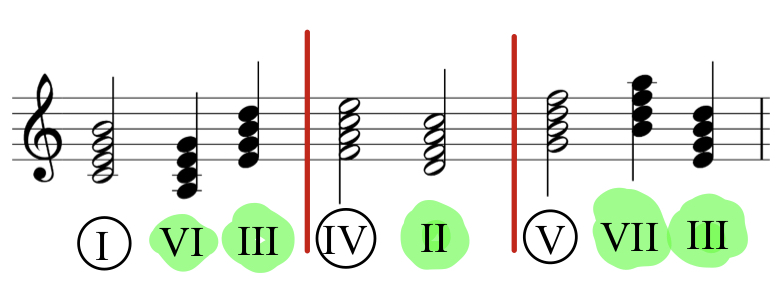

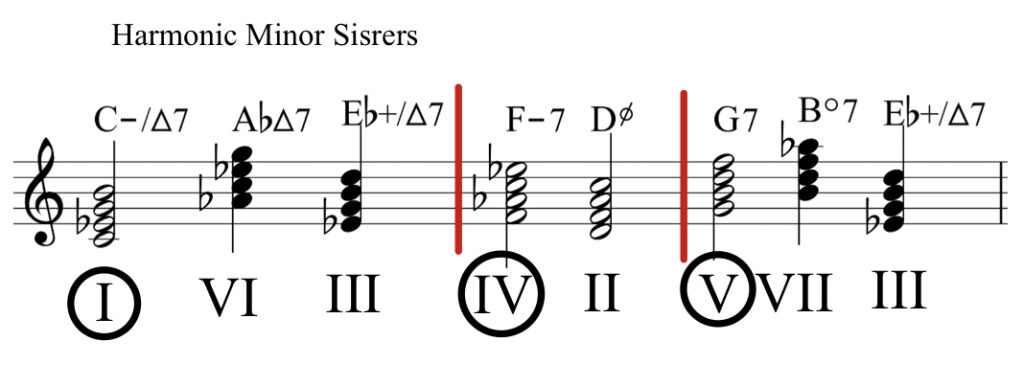

The remaining four chords in the set are all related to I, IV or V. We call them “Sister Chords” because they share 3 of their 4 notes (Example 3). VI is a sister to I (c, e and g are common). II is a sister to IV. VII is a sister to V. The III chord is unusual because it is sister to both the I and the V chord. Because these chords are so closely related they can perform similar functions.

Here are some examples of songs using Sister Chords (click on the song title to take you to the example): Time to Smile, Donna Lee, No Problem, Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.

That covers the basics of Destinational Tonality as it relates to Jazz. We can now move on to look at some “Traceable Movement” (Link) which will help us get ready to improvise on some songs.

The Blues

The Blues is an essential element in all types of Jazz, from Louis Armstrong to Ornette Coleman and beyond. Here are three important ways the Blues informs Jazz music:

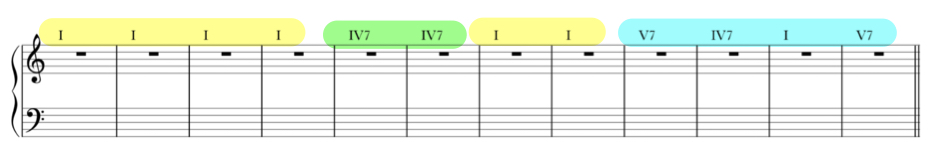

(1) Form – if a song is 12 or 8 bars long there is a good chance the Blues is part of the song’s structure. Foundational Blues uses the three basic chords of Destinational Tonality (I, IV and V). For more on Foundational Blues look here (Link).

(2) Flex-tones – we discuss the blues scale and flex-tones here (Link). (3) Dominant tonality – the flat three and flat seven of the blues scale gives us some useful chord alternatives to those offered by strict diatonic harmony (Example 5). This chord set has four dominant seven chords and three minor type chords. These are a big part of the “jazzy” sound of most 1940s and 50s styles.

Examples of Blues based Jazz: Gospel Truth, Doodlin’, Dig Dis, Freight Train, Relaxin’ at Camarillo, The Jody Grind. Squawkin’.

Minor Jazz

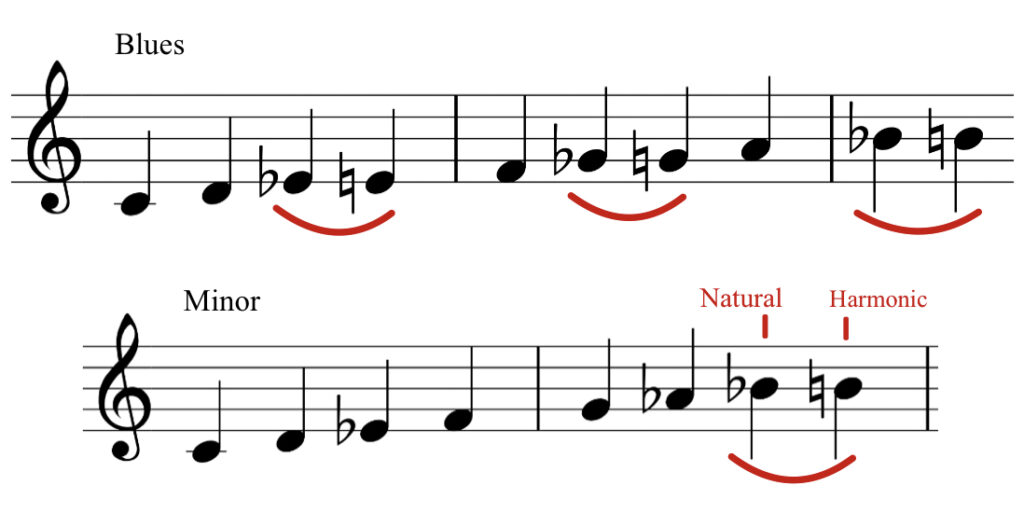

Minor Scales are quite similar to the Blues scale (Example 6). Jazz musicians have always looked at rules as a challenge so it is not surprising they have treated Minor tonalities rather loosely; often freely mixing the various scales (Natural, Melodic and Harmonic minor), even mixing Major and Minor. Example: The Jody Grind.

The chord set for Harmonic Minor (Example 7) opens up a whole new set of chord options. Particularly lovely is the tonic minor with a Maj7.

Here are some examples of Minor blues pieces: Nica’s Dream, Jordu, Whisper Not, Moanin’, No Problem. Goodbye Porkpie Hat, Erato.

Modulations

Technically, a modulation is a wholesale move from one tonic (key centre) to another with all its new relationships and functions. It’s like packing up all your stuff and moving to another house. For a modulation to count you need to drive around the new neighbourhood and maybe even visit your new cottage! Example: Prince Albert, No Problem, Joy Spring.

Ok, let’s go on a few road trips and look at some common Jazz changes.

Cycle Chains

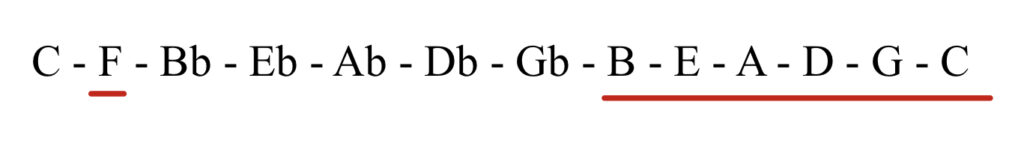

‘Cycle Chains’ are literally a “perfect road trip”, made up of perfect fifth or perfect fourth root movements (red notes). Notice in Example 8 the only chord in the set not in the chain is the IV chord, demonstrating its unique function as a “home away from home”.

If you flatten out the Cycle of Fifths (Link) into a line (Example 9) you can see the IV chord in ‘C’ is right beside the ‘I’ chord showing how it is a “Traceable Movement” to go straight from I to IV like in the blues. Going from IV to I is called a Plagal Cadence or an “amen cadence”.

Some examples of Cycle Chains: Bootin’ It, Joy Spring, Mile Ahead, Reflections, Hallucinations.

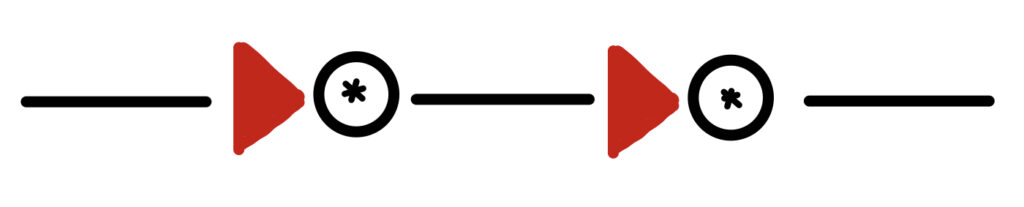

Temporary II - V Chains

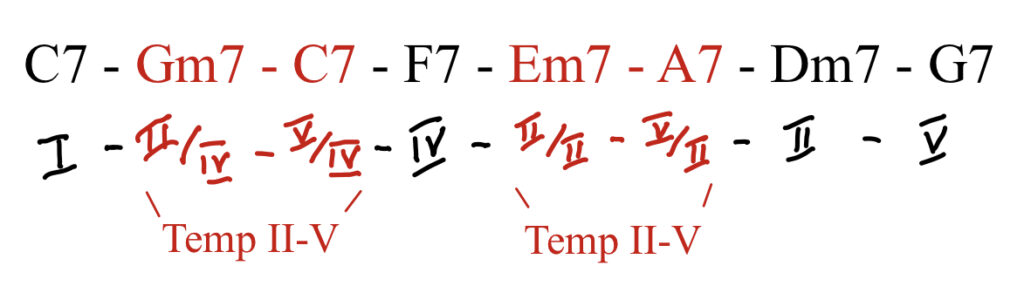

These little mini chains serve to strengthen the “Traceable Logic” of a progression. It’s like driving up the driveway of a chord that is not the Tonic. They pre-announce the arrival of a chord. For instance (Example 10), instead of going from I to IV you can go from I to the II of the IV chord to the V of the IV chord and then to the IV (C7-Gm7-C7- F7). The composer can approach any chord that he wants to emphasize the direction of the changes.

There are countless examples of this. Here are a few: Billie’s Bounce, Freight Train, New Rhumba, Whisper Not.

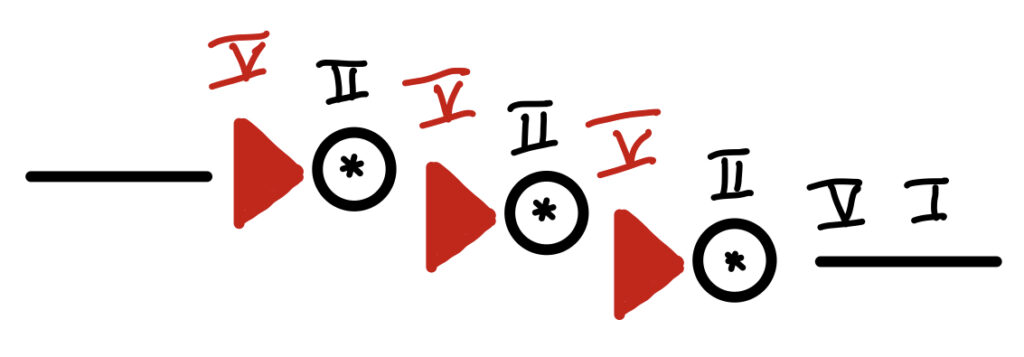

Unbroken Chains

Sometimes you will see a II-V chain that continues in a pattern. Our example (Example 11) shows a stepwise progression from F# to C. Each step is preceded by a V. Again, this drives the progression with more tension and urgency. The base steps don’t need to be stepwise. Coltrane used this trick with great effect on ‘Giant Steps’, but we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Examples: Bootin’ It, Isotope, Self-portrait in 3 Colours. Giant Steps.

Segmented Chains

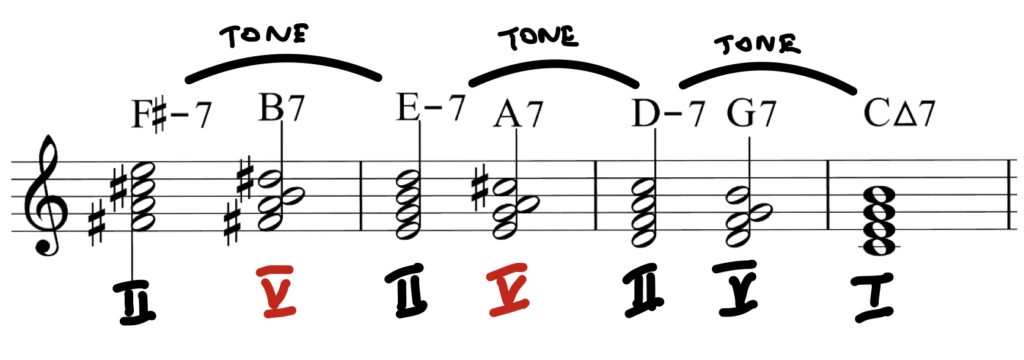

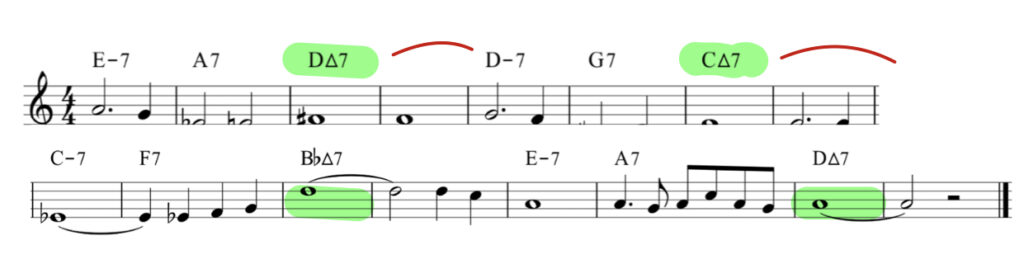

The Segmented Chain is kind of the opposite of an Unbroken Chain. It’s a chain of II -V – I patterns that rests on the temporary I chords. A little sleepover. Example 12 is from a Miles Davis head called ‘Tune-Up’. The basic direction is in whole steps again (D – C – Bb) but this time each step is a definite resting place.

Examples: Joy Spring. Recorda Me, Central Park West. Who Killed Cock Robin.

Dominant Substitutions

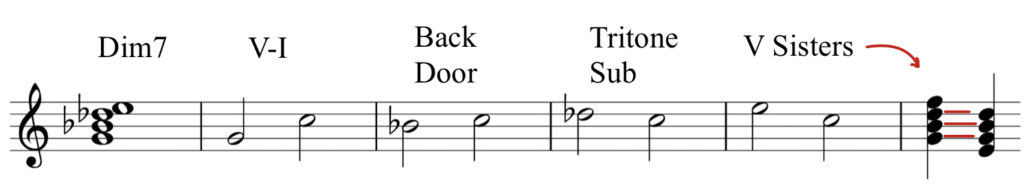

Example 13 shows us six cadences: The first is V – I, the “Perfect Cadence“, arriving at the tonic by a perfect interval (G – C). Straight up the driveway. (2) We have already mentioned the “Plagal Cadence” (IV – I). Three and four are Sister Chords of V. The other three Dominant Substitutions are all easy to pick out on a lead sheet because they all approach the Tonic by a step or half step. These kind of “Proximity Changes” become very important in the second part of this analysis.

Number five is the versatile Diminished Chord which we will have more to say about in a moment. Number 6 is a dominant chord built on bVII. It’s called a ‘Backdoor Cadence“. The last is a dominant chord built on bII, it’s called a “Tritone Substitution“. The “Aural Logic” of these substitutions rely on Voice Leading. Step wise movement is “understandable“.

Examples of Tritone Substitutions: Donna Lee, Boplicity, Ask Me Now, St. Vitus Dance, Pensativa, Penthouse Party, And Now the Queen, Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love,

Examples of Backdoor Cadences: Bye Ya, Monk’s Mood, Crepuscule with Nellie, Goodbye Porkpie Hat, No Problem.

The Diminished Seven

The Diminished Seven is like the Swiss Army Knife of chords. We went over the basics when we discussed the minor thirds group (Link): (1) it’s symmetrical (2) it contains a tritone and (3) starting on any note a Dim7 on I, IV and V together contain all the notes in the chromatic scale. Functionally, the chord offers many opportunities. (Note: enharmonic equivalence is very important here)

(1) If we look closely (Example 14) we can see that all the notes of a dim7 built on V gives us an alternative dominant substitution. A dominant built on the lowest note is V, a dominant built on the second note is the back-door cadence, on the third note we get the tritone sub, on the fourth we get the sister chord III.

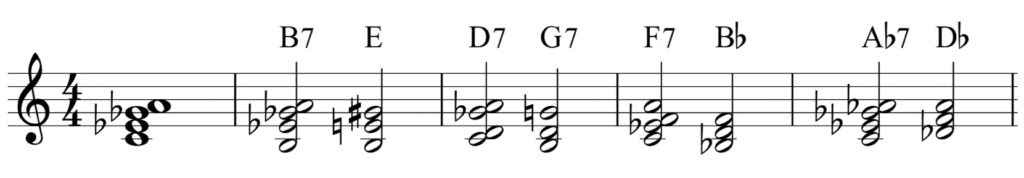

(2) Diminished chords work as Pivot Chords. From any Dim7 you can move off in four different directions. Example 15 shows us how, by dropping just one of the diminished chord notes by a semitone, we make a V Chord of another key. So the first one can seamlessly move to A (B7 – E – A or dim7 – V – I) the second moves to C, the third to Eb and the fourth to Gb.

(3) Finally, John Coltrane showed us how a dim7 chord can create structural markers that form Traceable Movement. Central Park West.

Toying with Chords

When doing Preparational Analysis be on the lookout for chords that have been modified for tension or colour while still retaining their function. For example, a II – V- I chain, Dm7 – G7 – CMaj7 might be altered as a:

D7 – G7 – C7 – Hallucinations, Who Knows.

DMaj7 – G7 – C7 – Monk’s Dream, Daahoud.

DMaj7 – GMaj7 – CMaj7 – Miles Ahead, Self-Portrait in 3 Colours.

Now! Let’s move on to some different approaches to Tonality (Link).

Carry on to Part 2 of Changes.

Back: Aural Logic.