Chapter 4, Part 2 - Compound Scales

Compound Scales combine various intervals in their construction, primarily tones and semitones. By far the most important compound scale is the seven note “Major Scale”. It is very loosely based on the overtone series.

There is no need to go into the overtone series and “equal temperament” here. Suffice it to say that after nearly 400 years of use it has become an inescapable aural reference point for us all. Composer and theorist Walter Piston went so far as to say “…play any little phrase they will hear it in some key; it may not be the right one, but the point is they will play it with a tonal sense. The more I feel I know Schoenberg’s music the more I believe he thought that way himself… and it isn’t only the players; it’s also the listeners. They will hear tonality in everything.”

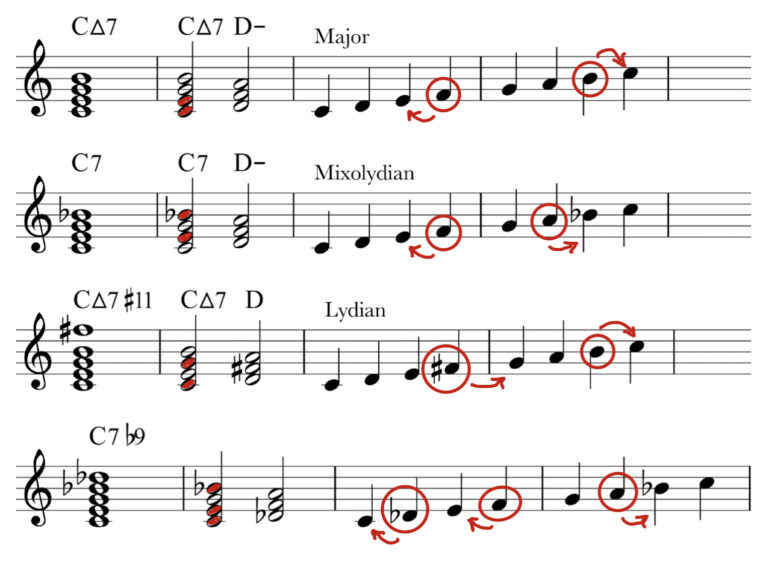

When we talked about chords (Link) we pointed out that by stacking thirds onto a “root” we create a triad with a 7, 9, 11 and 13 extension. Technically, the stack in Example 1 is called a C Major 7, 9, 11, 13. Because the 9, 11 and 13 are unaltered (diatonic) it would usually just be called a C Maj7. It can also be described as a CMaj7 with a D minor triad on top. The stack describes all the notes of a C Major scale. The scale is made up of tones and semitones. The circle and arrow show us where the semitones are. The two notes coloured in red (c and e) are the notes that the semitones pull to. Some scales pull to the root with a “leading tone” and some do not. Scales that pull to the root emphasis the key more.

Altered Compound Scales

The Major scale can be considered “foundational“. All the traditional “rules” of Western tonality are based on how the notes of this scale interact. The Chromatic scale is, of course, also foundational as it describes all the tones in the equal temperament system. The “Minor scale” can also be considered foundational but many Jazz compositions treat it as an “altered scale”.

When we change one or more of the notes in a major scale we get an ‘Altered Compound Scale’. There are hundreds of possible altered compound scales and creative musicians should always be on the lookout for interesting ones. Obviously, some of these scales are used a lot more than others (minor for instance).

Every musician will bank these scales in the mind differently. I prefer to name scales as little as possible. For example, the Mixolydian mode is the same as a major scale with a lowered 7th degree. I prefer to call this as a “major scale with a lowered 7th degree”. For me the name is irrelevant. I will show you why.

One of the basic skills for (most) Jazz musicians is to be able to read and interpret the chord symbols found on “lead sheets”. In most cases the chord symbols describe a “workable” scale, Example 2 shows us some chords and their related modes. The first bar of each line shows the root position chord as indicated by the chord symbol. The second bar shows the base chord with its implied extension. Bars three and four of each line shows the implied tone palette.

It should be obvious from this example that most scale names are redundant and unnecessary. To say that “you should play a Lydian scale over a CMaj7#11 chord” is obvious whether you know what a Lydian scale is or not.

The last line of Example 2 has a tone palette that does not have a name (at least one that I am aware of) but the palette is still obvious from the chord symbol.

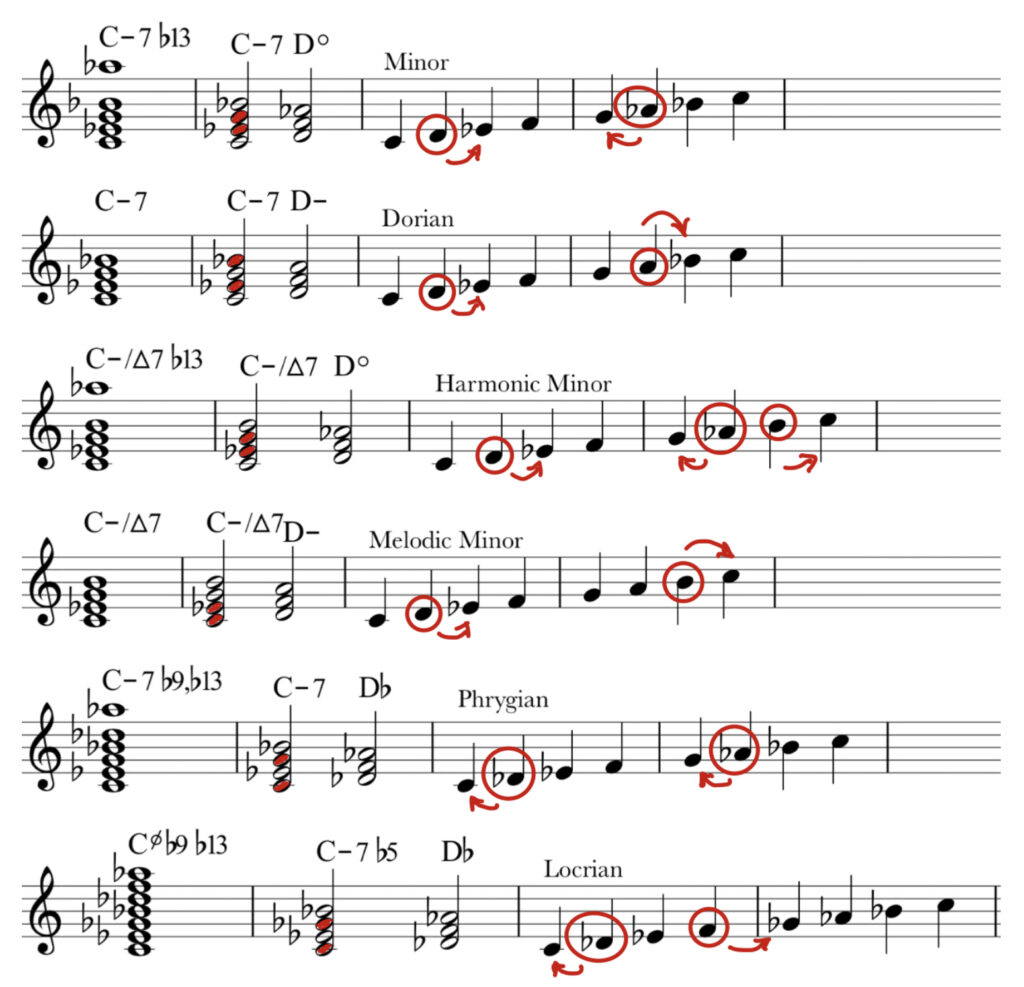

Example 3 shows a set of scales all of which have a minor 3rd. Again, the chord symbols tell the story.

As we work through ‘Our Analysis’ we will look at how minor scales relate to major scales and how the minor key is used in actual Jazz songs (Link).

Stylistic Scales

The last group of scales is what we call “Stylistic Scales”. They are contrived scales, created by analysts in an attempt to describe a particular style or technique. In most cases we believe it is far better to study compositions and solos directly rather than try and squeeze meaning from these scales.

The Blues Scale

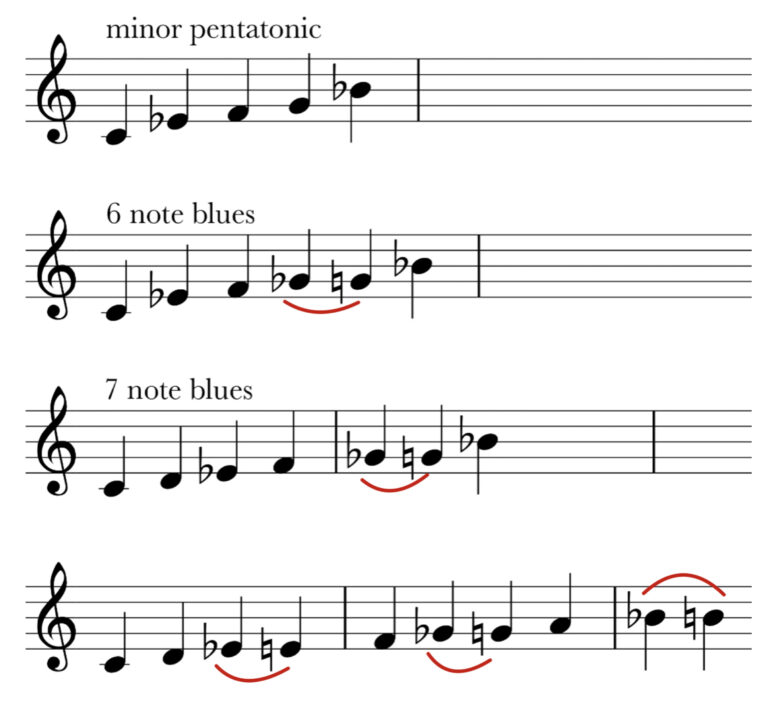

Blues musicians love to sing and play notes that “fall between the keys” of a piano. The microtones, slides and bends found in blues music don’t fit into the Western tonal framework. We can call them “Flex-tones“. Blues scales are all about trying to compensate for the systems shortcomings.

Blues scales begin with a pentatonic scale. This is not surprising as five note scales would have been familiar to all early American immigrants (both voluntary and involuntary) and the guitar is tuned to a kind of minor pentatonic scale (e-a-d-g-b-e / 1-2-b3-4-5). From here notes are added to show how musicians have treated the 3rd, 5th and 7th degree of the scale. We call theses notes Flex-tones. On instruments capable of altering the frequency of a note (guitars, horns etc.) the 3rd, 5th and 7th are often bent flat, or manipulated in some other way that sounds both the flat and natural or something in between (marked in red).

Blues players do not normally “compose on the spot” as Jazz players are expected to do; rather they normally involve themselves in the manipulation of the familiar. The audience for blues expects the musicians to combine phrases that they are already familiar with in interesting ways. Learning some of these signature passages of your favourite blues players will probably get you there quicker than playing around with the scales.

The Bebop Scales

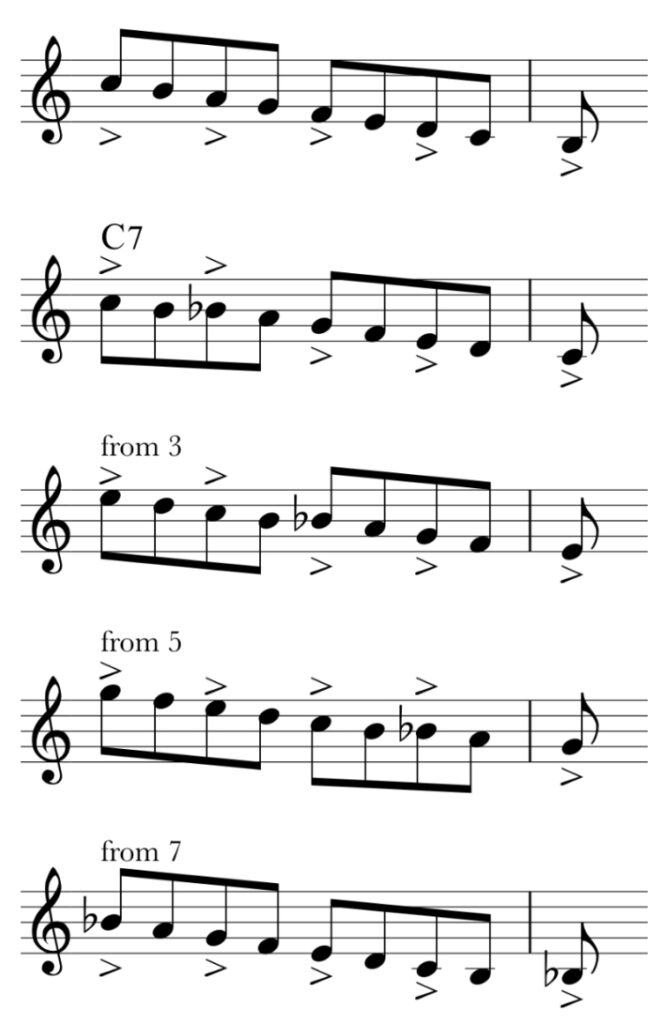

As the name implies, “bebop scales” reflect a style popularized in the late 1940s. A bebop scale creates symmetry by changing a seven note scale into an eight note scale.

The first line of Example 5 shows a descending C Major scale in eighth notes. The accents show where the down beats fall (1-2-3-4). If this line is played over a CMaj7 chord all the chord tones (c, e, g and b) fall on the weak offbeats.

Line 2 shows that by adding an extra note to the 7 note scale we shift the chord notes onto the strong downbeats. It’s a cool trick. Lines 3, 4 and 5 shows that it also works when the line is started on any chord tone.

There are bebop scales for other chords (Major 7 and minor 7) but they do not work quite as well. One way to remember the three scales is on minor (II) and dominant (V) chords use both 7 and b7 of the chords. On major 6th (I) use both the 6 and b6.

Check out ‘Our Analysis’ of ‘Donna Lee’ for a real life example of keeping the chord tones on the beat and some other bebop devices like turns, enclosures and and leading tones (Link).

The Altered Scale

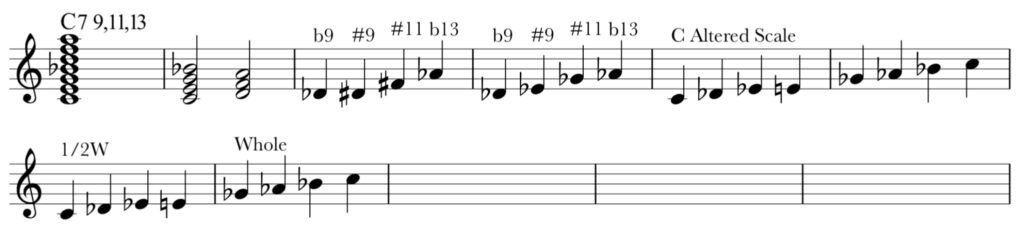

The last Stylist scale we will look at has come to be known as “The Altered Scale” (it’s also called “Altered Dominant” or “Super Locrian”). It might be the ultimate in contrived scales. In keeping with our approach of combining chord and scale theory, we begin with the idea of a 7th chord and it’s upper structure.

Example 6 begins with a dominant 7 chord with a diatonic upper structure. We then see all the altered 9, 11 and 13 notes possible with their enharmonic spellings in bar 4. Using all the altered extensions in a scale gives us The Altered Scale. We end up with a “Flex-tone” third (e flat and e) and a b9, #11 and a b13. If you prefer, you can think of it as a b9, b5 and b13.

Example 7 shows another interesting thing about this scale. It is a dominant shell (c, e, b flat) with a stack of fourths above. This can be used when constructing chords for this palette. Remember, the sound of quartal harmony was popular in the 1960s.

Eric Dolphy’s composition ’Les’ is a great example of this scale in action (Link).

Conclusions

(1) It is helpful to think of a scale as a “Tone Palette” rather than an ordered series.

(2) The function of scales depends on a musicians goals.

(3) Intervals are primary. Scales are derivative. Stacking intervals is a good way to approach scales.

(4) Chord symbols often describe scales. Find tone palettes that work over chord progressions by looking for tonal colours that complement all the chords.

(5) In many cases it is better to study compositions and solos rather than scales.

(6) For Creative Musicians there are no wrong notes but there are notes played disagreeably. Think of your “mistakes” as opportunities.

Back: Symmetrical Scales.

Next: Aural Logic.