Upper Structure Triads

Upper structure triads offer a multitude of ways to enhance the colour and functionality of chords. Let’s see if we can put together a systematic approach to understanding and choosing the 9, 11 and 13 chord extensions.

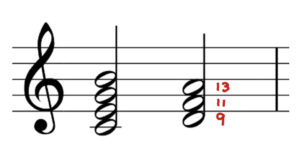

We covered the basics on our Chord Identification page (Link). Stacking thirds gives us a seven note chord before the pattern begins to repeat itself (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13). We pointed out that finding the diatonic upper structure for any chord is easy: play a minor triad a whole step above the root of the foundational chord (Example 1).

Along with the diatonic extensions there are four possible altered extensions: flat 9, sharp 9, sharp 11 and flat 13.

Note: A flat 11 is the same as a Major third (f flat = e natural). A sharp 13 is the same as a flat 7). This means there are twelve possible upper structure chords (Example 2). There are Major, minor half diminished, diminished and indeterminate chords in the collection.

A quick note before we continue: You will eventually come across a chord symbol like C7Alt. On its own it’s not terribly informative. It means the upper structure is “altered” but does not say how. The accompanying melody will usually show you which notes are altered and how.

The designation should really be reserved for a true “Alt. Chord” as it relates to “The Altered Scale“, meaning all the possible alterations are employed (Link at bottom of this page).

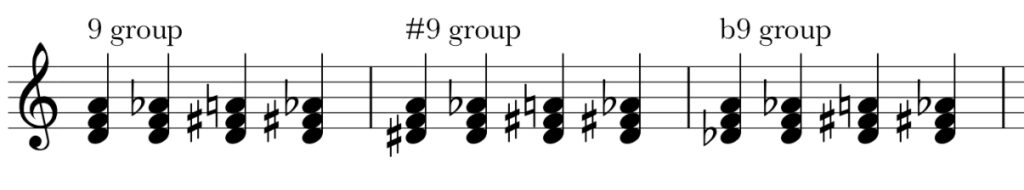

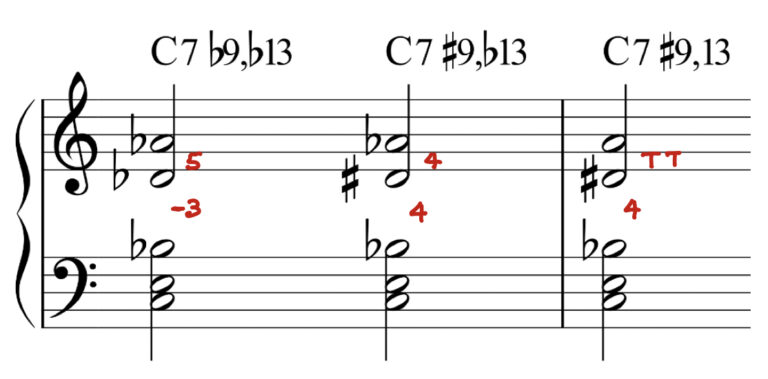

How we think about these chords comes down to personal preference. We can organize them into three groups based on which 9th is involved (Example 3).

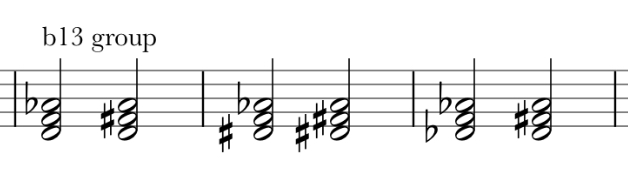

We could also arrange them into a sharp 11 group or a flat 13 group (Example 4).

Try playing each chord with just a root ‘c’ in the bass.

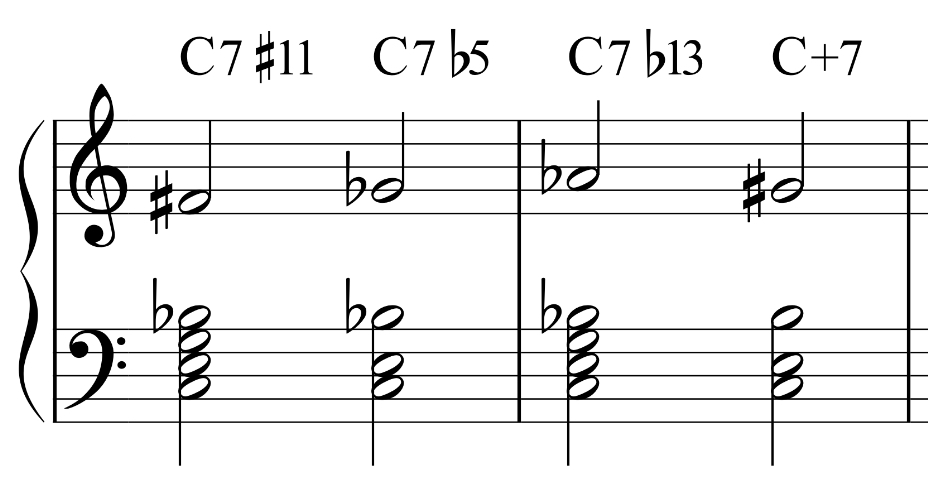

Before we move on we should mention something about the #11 and b13. The fifth of a four note foundational seven chord Is optional. It is not necessary to play this note to “name” the chord (1-3-7 tells the story).

If the fifth is absent the #11 can be viewed as a flat 5 and the b13 is like a sharp 5, making the chord augmented (Example 5). Remember, the b5 is an important bebop device.

Playing Around With Upper Structures

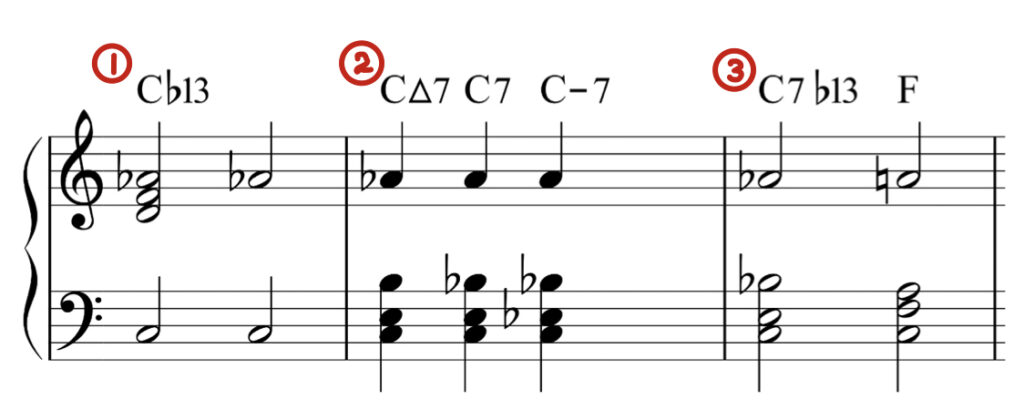

As I mentioned above, try playing the root of the foundational chord with different upper structures. Also try leaving off the diatonic parts of the upper triad (Example 6 Number 1)

Play the extension with different foundation chords (Example 6 Number 2)

Try the extension in a progression. If the foundation chord is dominant try a V-I cadence (Example 6 Number 3). If it’s minor do a II-V-I (Cm7 – F7-Bbmaj7).

Make note of which Upper Structures you consider High, Medium and Low Tension. Example 7 shows us three chords with a 9th and 13th on top. The first has, starting at the 7th (b flat), a minor third and Perfect fifth on top. Unsurprisingly, this is a relatively low tension chord. The second chord has two Perfect fourths on top, giving it mid-level tension. The last chord has a fourth and a tritone on top. As you might expect, the tritone generates a lot of tension that wants to be resolved.

Explore the melodic opportunities of the extensions. For example, the C7#11,b13 in Example 8 implies a whole tone scale. Rather Monk-ish!

Keep in mind the relationship of the extension to the Blues scale and Flex-Tones (see the section on ‘Stylistic Scales’ Link). A #9 can be viewed as a b3 flex-tone on a dominant chord. A #11 can function as a b5 flex-tone to the 5 (Example 9).

There is a lot of information here. Take it slow. Pick one or two extensions and work with them for a week or so. Listen to how the masters have used these extensions (see the section on “Upper Structure Extensions in Context” – Link). This is a huge reservoir of opportunities when you are arranging, improvising or doing Preparational Analysis.