Introduction to Modal Jazz

In the late 1950s and early 60s a diverse group of forward thinking musicians including Miles Davis, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock were exploring ways to allow improvisers more freedom of expression in a group setting.

In 1959 John Coltrane recorded the song ‘Giant Steps’, one of the most challenging set of chord changes an improviser can try to traverse (Link). Whether it was meant to or not, it punctuated the need for a more welcoming backdrop for improvisation. Another song on the same album offered one solution to overly restrictive heads – ‘Naima’ is discussed here (Link).

Just two weeks before these two songs were recorded Coltrane participated in a Miles Davis session that would be released under the title ‘Kind of Blue’. One of songs from that session was ‘So What’ (Link). This relatively simple architecture inspired what would later be known as “Modal Jazz”. Modal Jazz is part of a broader type of Jazz we call “Open Forms” (Link).

Background

One of the basic tenet of these discussions is that Jazz musicians involve themselves in “toying with a listeners expectations” (Link). As the 1950s evolved, the language of artists like Charlie Parker and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers became as fundamental to new players as the music of the Swing Era was for Parker.

This familiarity with the language of the 1940s and 50s lead to musicians like Ornette Coleman surprising his listeners by toying with the expectations created by Charlie Parker’s music.

We also noted that familiarity with a language allows musicians to “expand, contract, omit, anticipate, extend and ornament” that language.

These two principles were at play in the development of “Modal Jazz”.

Components

(1) A minimalist structure

One of the most striking features of “Modal Jazz” is economy. The heads are, more often than not, somewhat static or “roaming” with a paired down harmonic structure. The minimalist architecture was meant to allow the improvisers room to add their own colour and complexity as they developed their solos. Innovators like McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock repeatedly make reference to “opening up the harmony” to allow more freedom for the improvisers.

(2) A de-emphasis of “Destinational Tonality”.

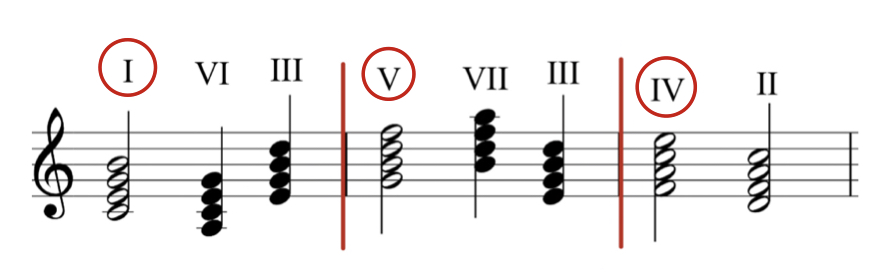

Modal heads tend to avoid established “jazz harmony” – that is lots of dominant 7 chords and V – I or IV-I groups. “Destinational Tonality” (Link) was often replaced with step or half-step bass movement or leaps like a minor third. It is important to note that, as a rule, soloists were quite happy to overlay the more traditional devices when improvising. We have a good example of this when we look at McCoy Tyner’s solo on ‘Impressions’ (Link). Again, the heads were minimalistic; the solos were anything but.

It is all well and good to avoid “Destinational Tonality” but these traditional progressions serve as points of reference for the listener – the music is “anchored” to something familiar. To quote the Groves Dictionary of Music: “Musical form in the narrow sense has ultimately only two basic aspects: Repetition and Recurrence.” Model Jazz often employed ‘Pedal Points’ as a repetitive anchor. The other common anchoring device was recurring bass movement – if a phrase used a minor third bass movement, the phrase was often repeated starting on another note, something we call “Paired Base Camps” (Link). The listener hears these recurring motifs as musical form.

(3) Multifunctional chords.

Three note clusters, triads, stacked fourths and the related suspended chords (symmetrical) were used extensively. These ambiguous voicings did not restrict the soloists. “I would leave space, which wouldn’t identify the chords so definitely to the point where it inhibited your other voicings, all the things you would use as substitutions.” McCoy Tyner

(4) The use of different modes other than Major (Ionian) and Minor (Aeolian).

It may seem strange to have modes last on the list of “Modal Jazz” components. This is because it is usually the least obvious feature to the casual listener (who among us heard Santana’s ‘Oye Como Va’ for the first time and said “oh yeah, that uses the Dorian mode!”)

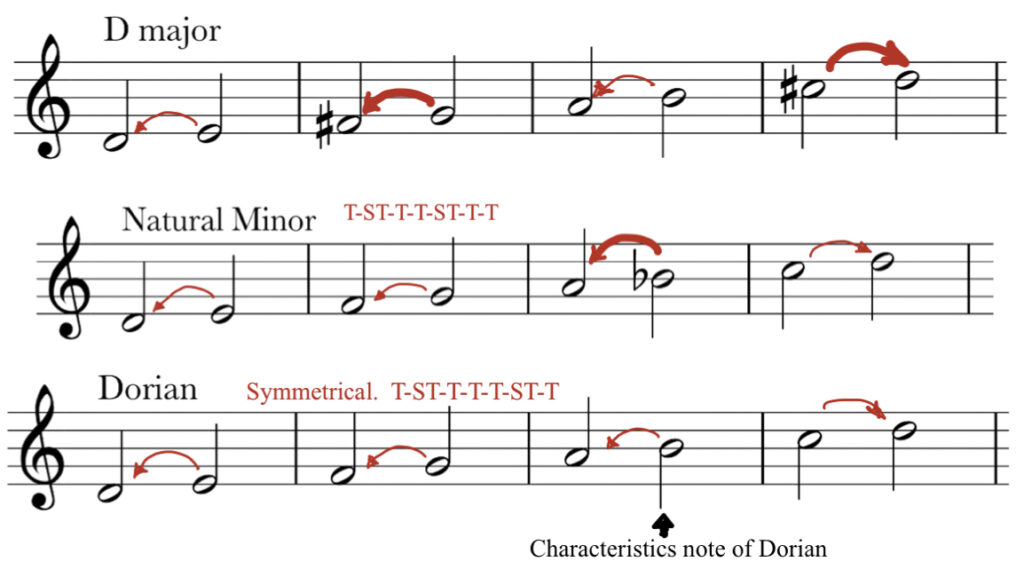

In keeping with the idea of “toying with expectations” I will look at a couple of modes as they relate to the “expected” major and minor scales. You will find lots of other ways to approach modes elsewhere.

The Lydian mode was important to George Russell who published a book about it in 1953. Russell made the argument that the fourth degree of the major scale did not “fit”. Russell argued that the fourth degree (the ‘f’ in Example 2) acts like a secondary tonic which, in fact, it does (Link). The blues plays off this unique relationship between the tonic and subdominant (Link). The 4th degree, if it displays any instability, pulls down to the 3rd. The Lydian mode with it’s #4 on the other hand, pulls up to the 5th. What’s interesting to me is that the sharp 4, or flat 5 forms a tritone. Monk loved a nice b5 (Link).

The Dorian mode has some unique characteristics that has made it a popular choice in Modal Jazz. It’s a symmetrical scale so the pull to tonic chord tones is weak – you might say it is a noncommittal scale.

The 6th degree is what distinguishes it from the minor scale.

Follow the link to hear some audio examples of what the Dorian mode sounds like (Link).

For a great example of how the Dorian modality works in comparison to the Harmonic Minor mode check out ‘Patterns’ by Ahmad Jamal (Link).