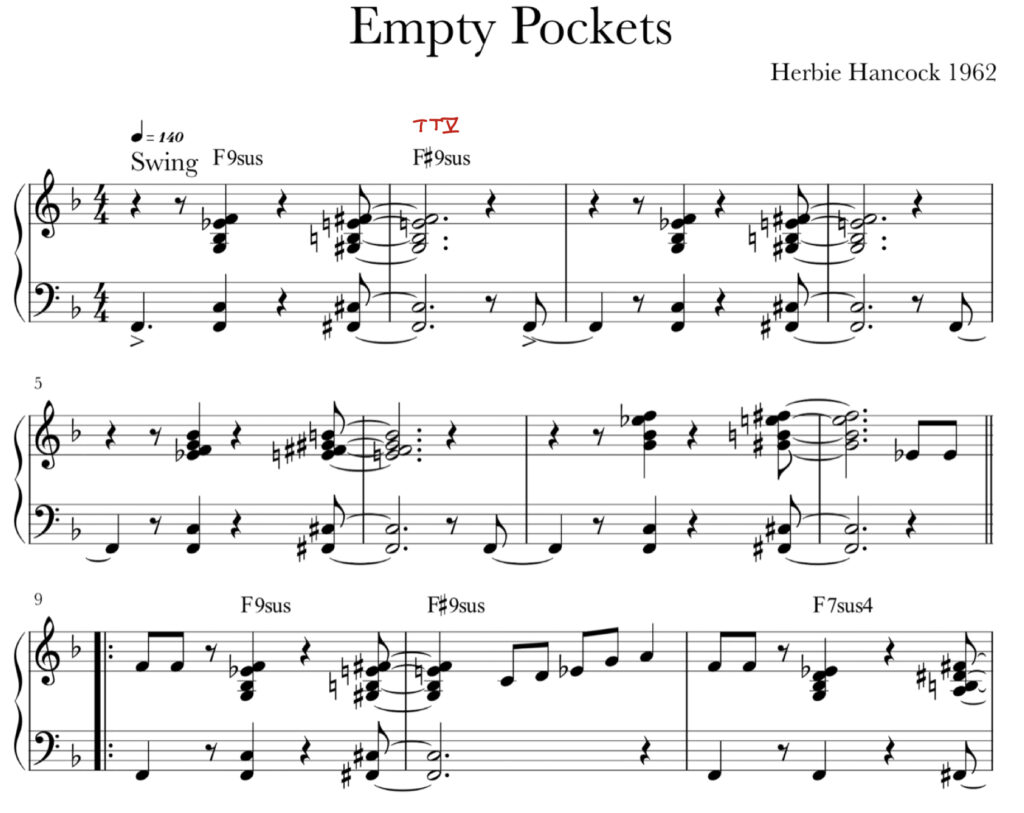

Herbie Hancock - 1962

Herbie Hancock’s ‘Empty Pockets’ is from the album “Takin’ Off”, his first album as leader. It is quite similar to Eric Dolphy’s ‘245’ in that they are both 12 bar blues compositions that mark the transition to the new innovations developing at this time.

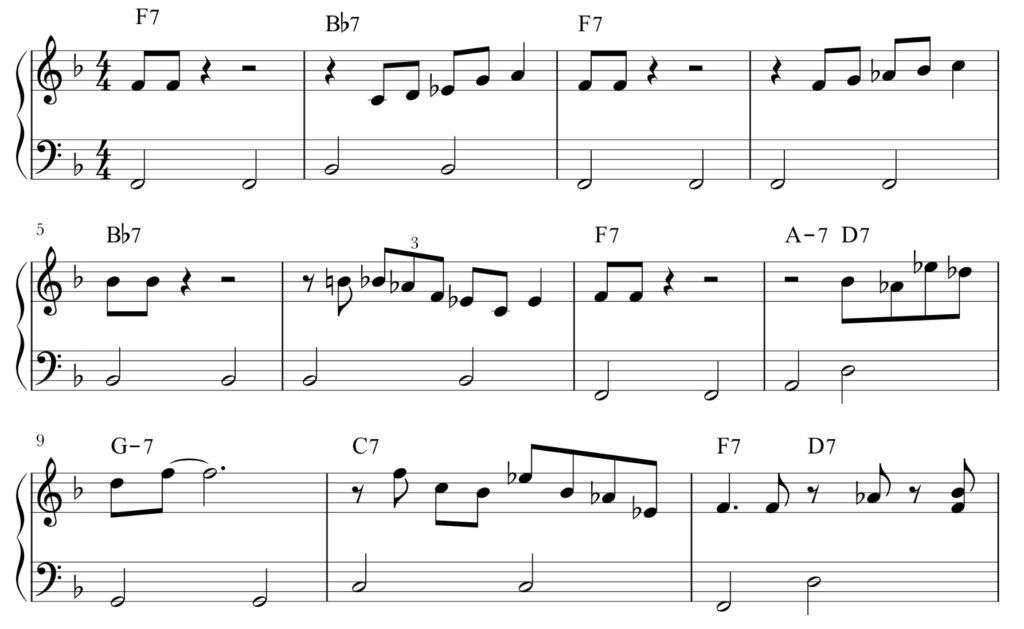

We will approach this song like we did with Eric Dolphy’s ’245’ (Link). Both pieces are 12 bar blues and they both have a distinctly “modern” feel.

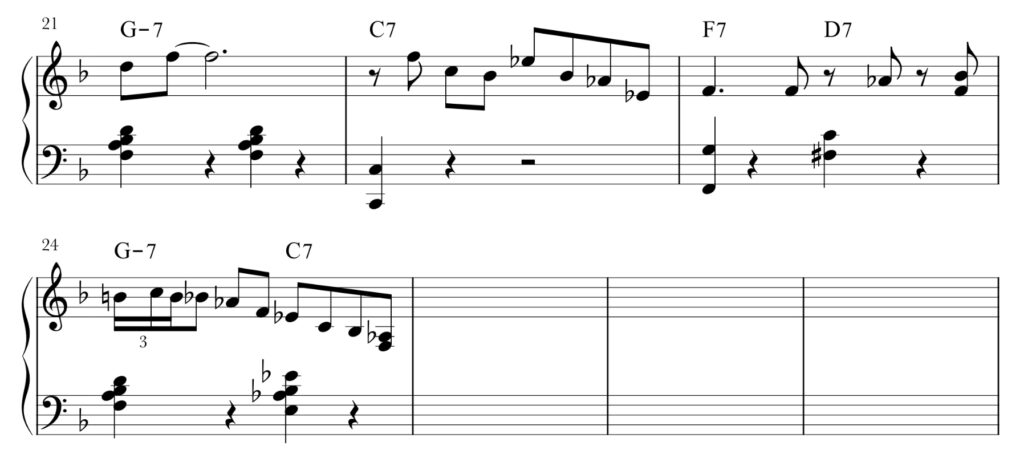

The first 12 bars of Example 1 show the melody over the root movement of a basic 12 bar blues (pedestrian but understandable). The next 12 bars show some of the left hand chords that Hancock employed when he took his solo. This approach of having a “different’’ sounding head followed by more familiar changes that the players can stretch out on was quite common.

What makes the piece special is Hancock’s treatment of the melody when they play the head, as we can see in the main transcription above. The first two bars use two parallel suspended chords a semi tone apart. We can look at these as a modified tonic chord followed by a Tritone Substitution for the V chord (Link). The chords themselves have lots of tension but the tension is added to because, rather than playing V-I, he plays I-V (replacing a “question-answer” with an “answer-question).

A similar tritone sub is employed in bar 12 above; this one sets up the shift to the standard blues IV chord. The chord in bar 16 is interesting. We call it F9,13 but it is really indeterminate because in root position it’s a stack of 4th intervals (Link).

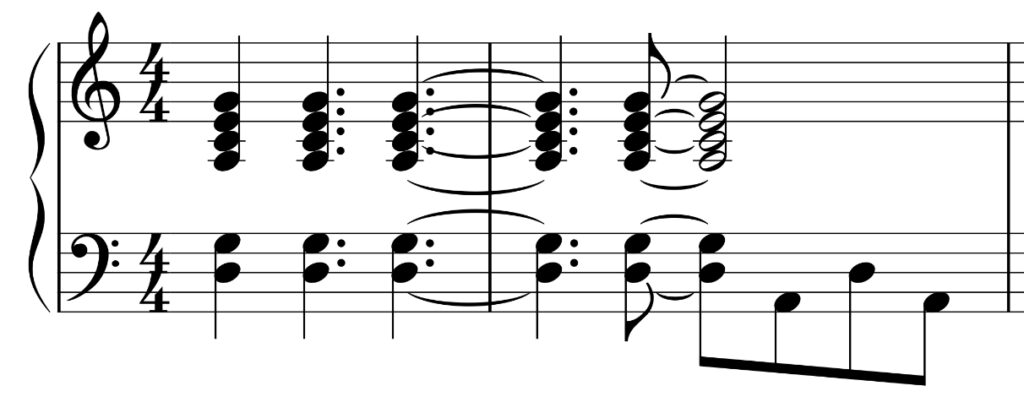

Herbie Hancock would go on to develop new ways of using the suspended fourth chord. The sound becomes synonymous with a style we call “Open Forms” (Link). Keep in mind: (1) these chords are indeterminate by design. You need to find a description that makes sense to you. (2) a suspended 4th chord is almost the same as an 11th chord (Link). There is a very interesting quote by Herbie Hancock concerning these suspended/eleven chords as he used them in his classic ‘Maiden Voyage’: “You start with a 7th chord with the 11th on the bottom – a 7th chord with a suspended 4th – and then that chord moves up a minor third… it doesn’t have any cadences; it just keeps moving around in a circle.“

The “Madian Voyage chord” in Example 2 is usually called either a D11 or a Dsus4 on lead sheets. But if we follow Herbie Hancock’s own analysis it is really an A7 11 chord with the 11th (d) in the bass! That’s an Indeterminate Chord for ya.