Chapter 6, Part 2 - Changes Two

In the quest to “get to a different type of improvisational area” Jazz composers began moving away from strict Destinational Tonality (Tension – Resolution) toward a looser interpretation that might be called “Free-Range” Tonality (Tension – Relaxation).

“Tonality does not exist as an absolute. It is implied through harmonic articulation and through the tension and relaxation of chords around a tone or chord base.” Vincent Persichetti

This “quest” led down three different paths during the 1960s and beyond. The distinction between these forms was not, of course, always clear. Composers and improvisers combined these forms freely but each style has some distinct qualities worth exploring:

Advanced Forms

New and more complex structures that are meant to challenge the improviser.

Open Forms

Free flowing structures that “get out of the way” of the improviser.

Collective Forms

Non-European structures grounded in “Roots Music” (early blues and West African music)

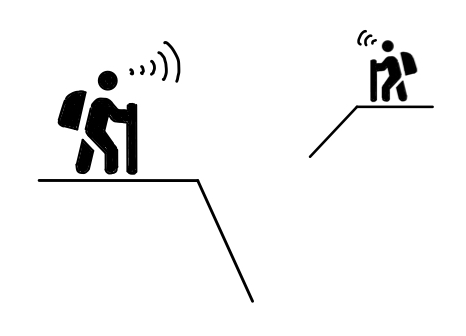

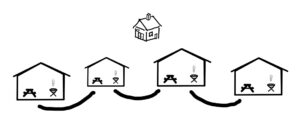

All three forms employ what we call “Markers” or “Pit Stops”. A Marker is a “linear reference point that reassures travellers that the proper path is being followed”. A Pit Stop is a “pause for refuelling, repairs, mechanical adjustments or a change of drivers”. These points of reference have been called Pitch Centres, Tonal Centres or Key Centres but these terms are more specific to a type of Advanced Structure.

Advanced Forms

The “Advanced Forms” still have Destinational Tonality at their core but interesting and surprising Traceable Movement (Link) abound which challenge our expectations. Some early examples of Advanced Forms can be found in the music of Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols. Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Andrew Hill, Joe Henderson, Eric Dolphy and Wayne Shorter are some of the composers that carried on the practice.

We can begin by looking at some of the harmonic and melodic trickery involved in these Advanced Forms:

(1) Chord roots loose some of their importance. Composers were using more complex, indeterminate chords (Link) with altered upper structures (Link). The “connective tissue” between these chords needed to rely more on their common or Guide Tones than on root movement. Example: Ask Me Now, Pannonica, When the Groove is Low, Self Portrait in 3 Colours, Miss Ann, Margot. Melodies are also more complex using not only arpeggios and steps but also more leaps. Example: 245.

(2) Along with using common chord tones to create Traceable Units, players might ground their complex harmonies in familiar chord shapes, such as the Bud Powell 7ths and 3rd left hand voicings. In destinational tonality these two note shells were the root and seventh or root and third of the chord, but in these advanced forms that might not be true. Still the shape is familiar giving the changes a traceable logic. Examples: Penthouse Party, Erato, Isotope, This is for Albert, Les.

(3) As with all forms of Jazz, repetition is crucial. Ostinatos and Pedals are often used to hold things together. Examples: Dial S for Sonny, The Maze, Potsa Lotsa. De-Dah.

(4) Players that were primarily supportive in earlier forms were now playing lead. These roll reversals have the highest voice creating a foundation while the lower voice contributes elaboration and colour. Example: Goodbye Porkpie Hat. Fuchsia Swing Song,

(5) Special mention should be made of #11 chords. They are found frequently in these Advanced Form pieces and lend a distinctive flavour (Link).

Let’s turn to some of the structural aspects of these Advanced Forms:

Delayed Resolution

This advanced structure still has one foot in Destinational Tonality. A tonic is arrived at eventually but resolution is delayed through a series of twists and turns. Examples: Pensativa, Introspection, Step Tempest. De-Dah.

Pitch Centres

I mentioned above that the idea of “Pitch Centres” is really a specific type of harmonic organization. It involves having pitches that act as points of relaxation (Pit Stops). “The tonic continued to exist, and, if necessary, the composer could employ it… but in the great majority of cases, he preferred the concept of a tonic in distant perspective.” Vavara Dernova.

Examples: The Gig, Recorda Me, This is for Albert, Blue in Green, Ode to Von. Coming on the Hudson.

Recurring Pitch Centres

Recurring Pitch Centres are more formally structured. The most famous example is the so called “Coltrane Changes”. The concept is arguably the apogee of the Advanced Form of Jazz Tonality. Example: Giant Steps, Central Park West.

Single Marker

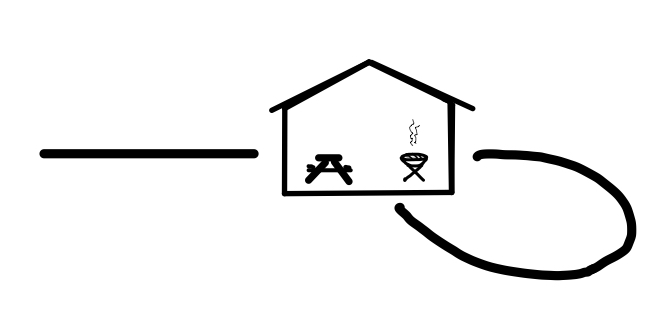

The “Single Marker” form is getting close to our next section called ‘Open Forms’. It uses just one recurring Pit Stop as a point of rest. Wayne Shorter’s ‘Free for All’ has a tonal centre of EMaj7. The A-section is a tonal IV-V-I but the intro and B-sections are both tension filled excursions. Andrew Hill’s ‘Erato’ has four bars that come to rest on G minor. This is followed by another four bars that take a completely different route to the same G minor marker.

Open Forms

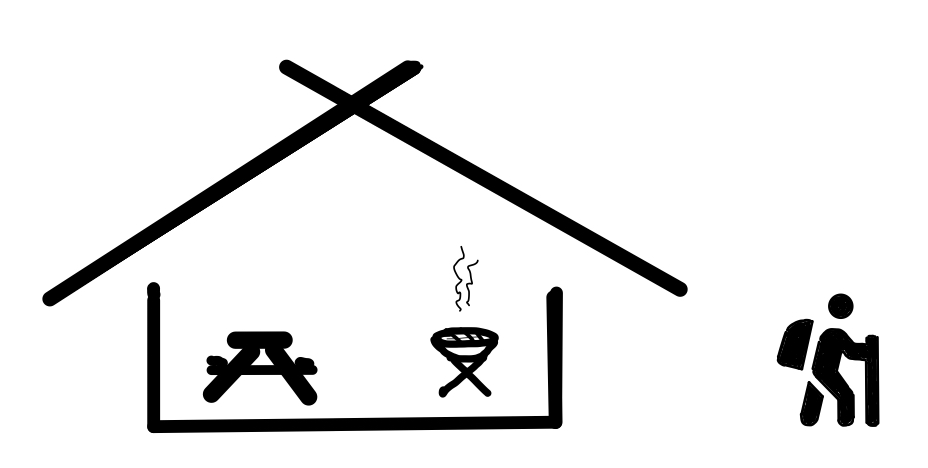

‘Advance Forms’ of tonal organization seem to ask the improviser: “Can you rise to the challenge?” ‘Open Forms’ try to answer a different question: “How can we create a head that is interesting harmonically but does not tie the hands of the soloists?” The answer, it turns out, was a relatively simple one. Some of the important practitioners of this form include Ahmad Jamal, Miles Davis, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock.

Tonal Areas

“Directional Tonality” is like going on a road trip with the whole family. The soloist and support musicians all move together through the changes. Open Form is like the family setting up a Base Camp while the improviser is free to explore the “Tonal Area“.

It’s interesting to see how McCoy Tyner goes on these excursions into different Tonal Areas. Check out the examples on Impressions and Passion Dance.

Setting up a Base Camp with Drones

The base camps are created by setting up different kinds of “Drones“. In classical Indian music the “drone is essentially the sounding of a constant melodic pitch or pitch sequence that underlines an elaborate melodic improvisation” indianetzone.com. All sorts of different music employ Drones (think Dulcimers, Bagpipes, Banjos and the Hurdy-Gurdy).

“Pedal Notes” or “Pedal Points” are the most obvious example of a drone in Jazz. John Coltrane was using pedal notes extensively just before he died, particularly on the recordings made with Alice Coltrane on piano. Example: Naima.

Rhythmic Bass Riffs and Call and Response Riffs are also common ways of setting up a base camp for improvisation. Examples: Ida Lupino, Free for All, So What.

“Modal Jazz“, is an Open Form style. For more on Modal Jazz check out this page (Link).

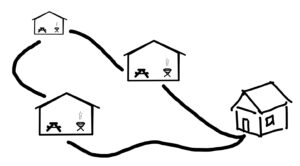

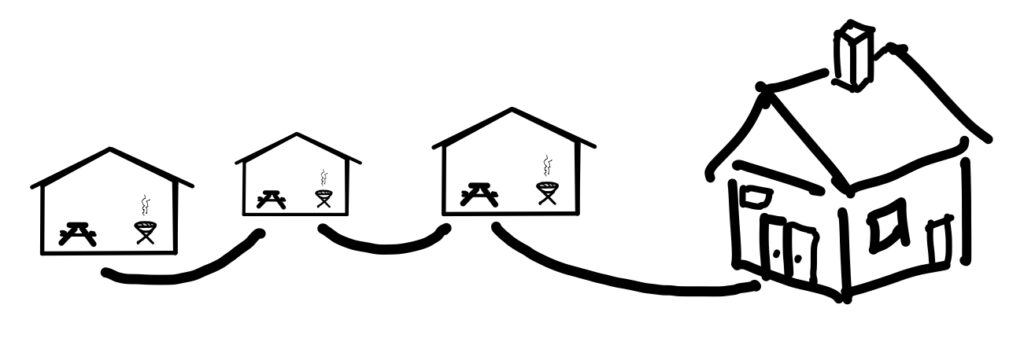

Paired Base Camps

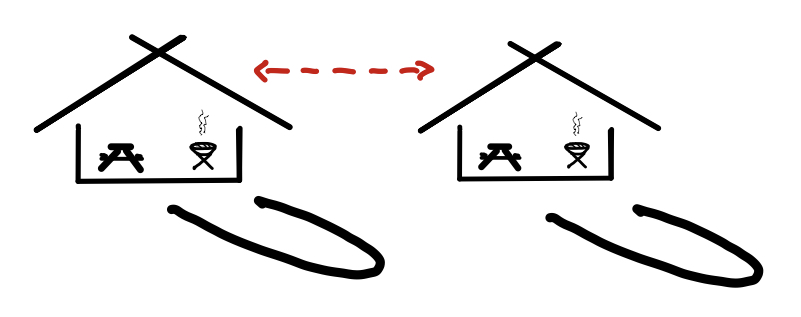

Base Camps most often come in pairs. The backing musicians stay in one Tonal Area for a fixed number of bars (4, 8, 12, 16…) then they jump without a tonal setup to a new area. The areas are often just a semitone away, this way the new area has a completely new tonal palette. Examples: Impressions, Passion Dance, Naima. Empty Pockets. Black Fire.

“It doesn’t have a cadence, it just keeps moving around in a circle.” Herbie Hancock talking about ‘Maiden Voyage’

Piano Solutions in Open Form

If piano players were no longer needed to run chord changes behind the soloist they needed to find other ways to participate. The bass player was quite capable of setting up the “drone” by playing ostinato patterns with pedal notes or riffs.

“I would leave space, which wouldn’t identify the chords so definitely to the point where it inhibited your other Voicings, all the things you would use as substitutions.” McCoy Tyner

One solution was to not play at all. On the first recording of Impressions, McCoy Tyner did not back up Coltrane’s solo. It became quite common for bands playing Collective Forms to not use a piano player.

Our Analysis of ‘Impressions’ goes into some detail about Tyner’s comping, using chords in 4ths and fifths and even some clusters. We also show how a non-directional support did not stop the soloists from employing Destinational Tonality.

Tyner, Herbie Hancock and many others used “Parallel Changes“, that is playing a chord and then moving the whole chord up or down, usually by a semitone or tone. This technique adds movement and interest without direction. Example: Patterns.

Another approach, exemplified by Bill Evans, was to concentrate on indeterminate chords that add impressionist colour and texture to the proceedings. Example: Blue in Green.

Special mention should be made of Mal Waldron who, over his long career, played in virtually every style. Around 1969, Waldron developed an elemental form of the Drone that was unique. Example: Down at the Gills.

There has always been economical composers and improvisers in Jazz: Count Basie and Duke Ellington immediately come to mind, but they were firmly grounded in “Destinational Tonality”. It was not until Ahmad Jamal that a clear way forward was demonstrated that would not only open things up spatially but also harmonically Example: New Rhumba.

Collective Forms

“Actually however, I don’t believe in freedom. I don’t think anything like that exists in the world or in music. I think there are higher laws – although, as you move under higher laws, you may operate under fewer laws, thus moving in a state of relative freedom as compared to being under numerous smaller laws. But there’s alway a law in Music.” George Russell

“Play any little phrase, they will hear it in some key—it may not be the right one, but the point is they will play it with a tonal sense. … The more I feel I know Schoenberg’s music the more I believe he thought that way himself. … And it isn’t only the players; it’s also the listeners. They will hear tonality in everything.” Composer Walter Piston

We began our discussion of ‘Changes’ with a rather formal definition of tonality. This Walter Piston quote offers a much looser way of thinking about tonality. I think what he is getting at is that after 350 years of organizing music tonally it has become woven into the fabric of our musical consciousness.

When we talked about Open Forms we used the analogy of a base camp and solo excursions from the camp. “Collective Forms” is more like everyone packing up their own stuff and going on the excursion together.

Some important practitioners include: Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Paul Bley, Mal Waldron, Albert Ayler and Archie Shepp.

“There are no barriers in our rhythm section. Everyone plays his personal concept, and nobody tells anyone else what to do. It is surprisingly spontaneous, and there’s a lot of give and take, for we all listen carefully to one another. From playing together, you get to know one another so well musically that you can anticipate. We have an over-all different approach, and that is responsible for our original style. As compared with a lot of other groups, we feel differently about music. With us, whatever comes out—that’s it, at that moment! We definitely believe in the value of the spontaneous.” McCoy Tyner

Let’s go back to basics for a moment and review the main components of “Aural Logic” (Link). (1) The main device that makes sound construction comprehensible is Repetition and Recurrence. (2) Traceable Movement moves between Imbalance and Stability. (3) The combination of Repetition and Traceable Movement creates Expectations.

Collective Forms tend to fall back on these basics. There is also extensive use of what we call “Free verse“. It is a term borrowed from poetry: “Non-metrical, non-rhyming lines that closely follow the natural rhythms of speech. A regular pattern of sound or rhythm may emerge in free-verse lines, but the poet (musician) does not adhere to a metrical plan in their composition.” Check out the page on “Pulse Drummers” to see how percussionists deal with the non-metrical aspect of Collective Forms.

Collective Forms also go back to the roots of Jazz. West African forms are used both rhythmically and harmonically. Early blues and simple folk songs are important. The style of Polyphony is usually Incidental or, Collective, as it was in early New Orleans Jazz.

The following table summarizes some of the differences between Directional Forms and Collective Forms:

| Aspect | Directional Forms | Collective Forms |

|---|---|---|

| Traceable Movement | Tension – Resolution Tension – Relaxation | Agitation – Calm Disturbance – Equilibrium |

| Polyphony | Supportive Structured | Collective Incidental |

| Rhythm | Period & Pulse | Pulse & Pattern |

| Tonal Palette | Altered Major | Chromatic & Pentatonic |

| Harmony | Root Movement Tertian Constructs Four Note Chords | Octaves, Fifths Indeterminates |

| Models, Influence | European 1940s Jazz | African & World 1920s & Earlier |

| Changes | Blues & Cycle Chains | Blues & Free Verse |

| Improv Framework | Head Changes | Imitation & Motifs |

| Acoustics | Personalized Timbre | Personalized Timbre & Unconventional Acoustics |

Personalized Timbre & Unconventional Acoustics

We use the terms “Personalized Timbre” and “Unconventional Acoustics” in the table. Personalized Timbre has always been important to Jazz musicians. Anyone familiar with the genre can name the performer after a few notes.

Many players of Collective Forms use a variety of unconventional acoustics to express themselves. These techniques include: overblowing, multiphonics, quarter tones, circular breathing, false fingerings, ghost notes, clicks, damping and growls. Bands like The Art Ensemble of Chicago used “found instruments” like toy whistles, gongs and noise makers.

“I listened to everyone I could hear to make sure I didn’t sound like them. I wasn’t taking any chances; I wanted to be sure I didn’t sound like anyone else. I’ve gone to great lengths not to, so I’m slightly offended when people compare me to this or that one. That means they aren’t listening to me. A person doesn’t have to sound like Charlie Parker or John Coltrane. It takes more work but it can be done.” Sam Rivers

Examples:

Here are some examples of the techniques used in “Collective Forms”:

Ornette Coleman – The Blessing, Invisible, Ramblin, Cecil Taylor – Lena, Indent, Aster, Mal Waldron – Down at the Gills, Carla Bley – Batterie, And Now the Queen, Eric Dolphy – 245, Les, Potsa Lotsa, Jimmy Lyons- Other Afternoons,